Part Two:

This is Part Two of this report; if you missed Part One, go back and read it first.

Done? Okay, then let's go on...

When we walked back up from the beach we found that the park rangers had put out a sign saying the beach was only open on weekends. They were a bit late.

We got in the car and headed back to Cave City, and it was either then or the night before, I'm not entirely sure which, that we ate dinner at a retro-chic 1950s-style diner. This is where we invented "I Have A Question."

After a second night at the Budget Host Inn in Horse Cave, we packed up, checked out, and drove off to Mammoth Cave National Park for our tour.

The Grand Avenue Tour is limited to 120 tourists, escorted by two rangers; ours were named John and Rachel. 120 is obviously a large group, but can be managed.

We collected at the Visitor Center, and were given the official warning that this was a strenuous tour -- four miles of walking, much of it up and down steep slopes, with lots of stairs, narrow places, etc. This might have seemed like overkill, but when we took the same tour back in 1979 there were elderly people, there were families with babies, there were preschoolers... people clearly hadn't paid any attention to the warnings on the tour descriptions, so now they really pound on it in the speeches.

(They've also set an age limit -- no one under age 6 allowed. A very good idea.)

There is exactly one place in the tour where you can drop out if you decide you don't want to do the full four miles. It's one mile in, at the Snowball Dining Room, at the lunch break; if you quit there they can take you up the service elevator. Unfortunately, that first mile is by far the easiest part of the tour, so some people who ought to quit don't, and once you're past that point there's no other way out without going the entire rest of the three miles -- the lights aren't on except where the tour is, so you can't backtrack.

I think one annoying woman did drop out of our tour at lunch -- at least, I didn't see her after that.

Mammoth Cave offers a whole slew of tours, ranging from incredibly short, wimpy ones to the dreaded Wild Cave Tour. The Wild Cave Tour goes five miles (or so; the route may vary) in six hours; you need to be at least sixteen years old, in good health, with a chest measurement of no more than 42". You bring your own kneepads; they provide the helmets and lights. The Grand Avenue Tour is about the longest one that's entirely on lighted paths; it covers all of the Travertine Tour, most of the Frozen Niagara Tour, and intersects the Wild Cave Tour several places. It doesn't go anywhere near the Historic Tour or any of the others I can think of right now -- remember, Mammoth Cave has over 350 miles of passages, and has twenty-three known entrances (most too small for tourists).

So. After the speech, they loaded us aboard three buses and drove us to the Carmichael Entrance. The Visitor Center is near the Historic Entrance, so-called because it's a great big obvious natural opening, the only one that looks like a traditional cave, that was the first entrance known. The Carmichael Entrance is not natural, and not near the Visitor Center; it was blasted through solid rock in 1931 by a guy named Carmichael who was something of an expert on caves, and goes down 200 feet to a big open passage called... no, not Grand Avenue; Cleveland Avenue. Cleveland Avenue apparently used to connect up to another part of Mammoth Cave, but a mile or so of the tunnel fell in a few hundred thousand years ago, leaving this big dead end, and Carmichael decided that was a good place to punch a hole down.

The above-ground portion is a walkway to a metal door set in a sort of bunker; there's no real building, no amenities, just a door. We marched through it and traipsed twenty stories down -- the first few feet through concrete bunker, the next hundred-plus feet through rough-cut rock, and the last forty feet or so through open cave.

Near the entrance we passed a sleeping bat -- just one, hanging on the wall, probably close enough to touch, though nobody did. It was a little tiny thing, looked hardly bigger than a caterpillar, brown and fuzzy and compact.

And finally we were in the cave.

Kentucky sits on a big slab of limestone that was once the bottom of the Mississippi Sea. Most of it is just that, limestone with a thin layer of topsoil. Around Mammoth Cave, however, it somehow acquired a sandstone "cap" about a hundred and fifty feet thick -- I'm really not clear on how this geological fluke occurred, but because it did, water flowing through passages in the limestone that would have been open river valleys elsewhere wound up as cave. There are places in the cave where you can see the sandstone as a flat roof far overhead -- it looks strange.

And in fact, the Green River and Mammoth Cave are the same system, with the difference being that the Green River isn't under sandstone and the cave is. When the Green River floods, so does Mammoth Cave -- as has happened in recent years; the fourth level of the cave is usually dry and suitable for tours, but there was one recent flood that had the third level awash. They no longer run tours to the fourth level as a result.

The Carmichael Entrance is cut through a hundred and fifty feet of sandstone.

When you get outside the National Park -- the park covers pretty much the entire sandstone ridge -- much of the land is flat; you're on the eastern edge of the Great Plains, not in the hills.

Officially, by the way, the river in Mammoth Cave is the Echo River, and it's a tributary to the Green River. The Echo River, however, is extremely convoluted, in three dimensions rather than the usual two.

Most limestone caves -- like Diamond Caverns -- are shallow, recent, and don't last all that long in geological terms. Mammoth is an exception, being large, old, and stable, and it's the sandstone that's responsible.

There are some other sandstone hills scattered around, and unsurprisingly, that's where most of the other caves are. Crystal Onyx Cave is halfway up a hillside, for example.

So we got down to Cleveland Avenue, and on one side was a huge pile of rubble called "the Rocky Mountains." The kids didn't even recognize it as anything but more cave wall, but it's probably what's left of that huge cave-in millennia ago. We were in a chamber about thirty feet high, forty feet wide, and two hundred feet long, at a guess. Here John collected everyone and gave his introductory spiel and question-and-answer session, covering some basics of cave formation, explaining the sandstone cap, and so on.

A couple of highlights:

- When he started working at Mammoth Cave in the fall of 1993 he asked about rockfalls in the cave, and was told that since the cave was opened to tours in 1816 (it was found by whites in 1799) there had never been any sort of fall -- not so much as a pebble. Well, a couple of months later, early in 1994, that changed. There was a huge ice storm and extreme cold, enough that water in the cave roof near the entrance froze for the first time in recorded history, and a sixty-ton chunk of ceiling fell, smack onto the path used by the Historic Tour. The storm had knocked out the power, however, and no lantern tours were scheduled just then, so there was no one in the cave at the time.

- In another incident, which we heard about both times we toured the cave, many years ago there was an earthquake -- that area doesn't get many quakes, but it did get one bad enough to crack windows and knock books off shelves. There were tours in the cave at the time. Rescue parties were sent in to be sure the tourists were okay. They were okay, all right -- they hadn't felt a thing. The earthquake had passed right over the cave without touching it. Some of them were furious at missing the quake.

- There have also been power failures while tours were down there -- one just a week before we were there, when a thunderstorm took down some lines. The guides carry flashlights, and there are emergency lanterns stashed along the tour routes, just in case, so it's no big deal.

And nothing exciting happened to us.

When the talk was done, the rangers led us on out of the chamber and into the avenue proper, where we got our first look at the gypsum.

The limestone around Mammoth Cave is laced with sulfur. Limestone is calcium carbonate; if you run water through a mixture of sulfur and calcium carbonate under pressure, you get hydrated calcium sulfate.

Hydrated calcium sulfate is gypsum -- that gray powdery stuff that's used in drywall.

Most limestone caves don't have sulfur or all that much pressure, and water that seeps in just carries dissolved limestone, which then crystallizes into onyx. At Mammoth, though, there's lots of pressure from the weight of the sandstone, and lots of sulfur. As a result, in much of the cave the moisture that seeps in carries gypsum crystals with it, and they build up on the walls and ceiling in lumps and streaks and bubbles and sheets. Sometimes the bubbles pop and curl back on themselves; sometimes the stuff is extruded in curls; and these can make gypsum "flowers." They're strange, and rather beautiful, and extremely fragile.

Indians used to mine Mammoth Cave for gypsum -- last I heard no one was really sure what the hell they did with it, but they definitely came in and flaked it off the walls. Also, a hundred years of tours lit by torches, candles, and lanterns put a good layer of smoke and soot on a lot of the cave's interior around the big natural entrance. Ignorant early owners also let tourists take gypsum souvenirs. As a result, in much of the cave the gypsum is gone or badly damaged.

Cleveland Avenue, though, is so far from the natural entrances that it's relatively untouched, and the walls and ceiling are covered in gypsum. In a few places it built up enough to pull loose from the ceiling in big slabs -- some fell to the floor and are still there, while others are still hanging, attached at one end. These slabs are typically a foot or two across, two or three feet long, and an inch or two thick, but they vary a lot.

The gypsum gives the avenue a curiously homey, finished feel -- it doesn't look like rock at all, almost; it looks like badly-finished stucco.

Cleveland Avenue, for which the Grand Avenue tour is named, is darn near level, amazingly straight, with a few gentle curves; it's oval, about eight to twelve feet high in the middle and about twenty feet wide. It's close to a mile long. The kids remarked that it was like walking through a subway tunnel, rather than a cave, and it's not a bad assessment. Yeah, the floor is broken limestone and hard-packed mud rather than pavement, but there are no stalagmites, no columns, no drops or breaks, no flowstone -- just smooth, gypsum-lined tunnel. Yeah, the gypsum's lumpy and sometimes patterned strangely, but still, it doesn't seem wild and natural.

But there were a few surprises.

I mentioned the Wild Cave Tour earlier -- fourteen healthy tourists and a guide, making their way through five miles of cave without benefit of paths and display lighting. Part of its route parallels Cleveland Avenue, but in a different passage -- a much smaller passage.

Well, as we were walking along Cleveland Avenue, this young woman's head, wearing a helmet and lamp, appeared out of a hole at the base of the right-hand wall. I hadn't even seen the hole there -- it just looked like a shadow, until she popped out.

She proceeded to pull herself up through a hole not much bigger around than she was herself, get to her feet, brush herself off, then trot off down Cleveland Avenue ahead of our tour group. She was wearing a dusty blue coverall, boots, and kneepads.

John the ranger explained that she had been on the Wild Cave Tour, and had decided she didn't want to take their route for the next part of the trip. I don't know if she quit and went home, or if she rejoined them later -- I suspect the latter, as the Wild Cave Tour makes the same lunch stop as the Grand Avenue Tour.

The woman popped up maybe a third of the way along Cleveland Avenue; about three-fourths of the way we glanced over to see light wavering around inside a hole in the floor, just to the right of the path. Sure enough, it was the rest of the Wild Cave Tour, making their way up into the main tunnel on the way to lunch.

The hole they were coming through sloped up into Cleveland Avenue from below at roughly thirty degrees off horizontal, at about a forty-five degree angle to the avenue wall; when there wasn't anyone in the way I could see that they were crawling up a tube maybe two feet across -- maybe less. Some shimmied right up; others panted and struggled and heaved, getting pushed from below and pulled from above.

We watched about half a dozen of them emerge; it was fascinating.

Then we marched on, leaving them to regroup by the hole -- we wanted to get to lunch before the lines got too long.

There was a stop just before the dining room, though, where John discussed the 19th century tours -- this was about as far in as they got, and there was a big flat rock (a fallen chunk of ceiling) that had been the original dining room, where slaves would set out a picnic lunch by lantern-light. John pointed out a shard of broken wine bottle.

Nowadays the meals aren't quite so elaborate.

The Snowball Dining Room was installed back in the 1930s. It's a room where three passages meet -- Cleveland Avenue, Boone Avenue, and one I forget the name of, except that it was something Egyptian. (One landowner used Egyptian names wherever possible for features in his piece of the cave -- "the Ruins of Karnak," for example. Another used a New York theme, which is why there's "Frozen Niagara.")

It's called the Snowball Dining Room because the ceiling has a lot of snowball-shaped gypsum formations. As John pointed it, it also has a bunch of gypsum formations that look more like someone threw wads of wet toilet paper around, but "the Toilet Paper Dining Room" didn't sound as good. I've heard that there used to be more "snowballs," but the soot and general racket and fumes from the dining area destroyed some of them.

The Park Service has done some clean-up there in recent years, and uncovered a wall of antique graffiti -- this was pointed out to us, but I didn't find it very interesting.

As for how they manage a dining room, someone sank a shaft through 267 feet of stone and installed a freight elevator and some plumbing. This is the only elevator into the cave; it's therefore where they run what used to be called the Wheelchair Tour, but has now been renamed something more inclusive -- I think it's now the Mobility-Impaired Tour. Folks using wheelchairs or walkers ride down the elevator and go a ways up Cleveland Avenue -- it's about the only place in the cave that's flat and level enough.

The old tours used to come in on the Egyptian passage, whatever it's called, eat lunch on the flat rock, then go out Boone Avenue; they didn't go up Cleveland very far, as it was a boring dead end.

The dining room is triangular. The center and the Cleveland Avenue point and the Boone Avenue point are full of picnic tables, and the third point is the serving area, with a cafeteria-style line offering cans of soda, bottled drinks, candy bars, cold sandwiches, and so on. If you want to save time you can just buy a complete box lunch.

They push the tuna fish, but we strongly recommend the ham and cheese.

We'd brought our own cans of Coke, in a backpack (along with a flashlight, a bottle of ice water, and other useful stuff), but we bought sandwiches and chips and candy bars and munched happily.

And the Wild Cave Tour arrived shortly after we did, and also munched happily just across from us. This was the point on both tours when anyone who wanted to wimp out could do so; I don't know if anyone did.

We didn't see the Wild Cave folks again after lunch; our paths diverged.

There's another important feature at the Snowball Dining Room besides food -- rest rooms. There are two sets of rest rooms on the Grand Avenue tour; this was the first. They're just around the corner on Boone Avenue, beside a gathering area equipped with benches where tours regroup before proceeding.

The unique feature of the rest rooms (aside from invisible details like pumps to get stuff back up to the surface) is that the ceilings and part of one wall are natural cave, with lots of interesting textures clearly visible, as the light's brighter there than on most of the tour.

Anyway, our group gathered and marched off down Boone Avenue.

I have never heard a very clear explanation of why Boone Avenue and Cleveland Avenue are so completely different, when they adjoin each other. They are different, though. Boone Avenue is narrow and winding, and free of gypsum -- you walk along between clearly-layered limestone walls that are obviously bare rock worn by water.

You walk single-file, at that, because there are places the entire passage is only two or three feet wide at shoulder height. Or waist height.

It's wider at your feet, and at your head, though -- the sides aren't anywhere near straight. A cross-section of either wall would look like a seismograph record of a mid-sized quake.

The widest part is up at the top -- but you can't see that very well.

That's because where Cleveland Avenue was tall enough for anyone but an NBA forward to walk through without stooping but always had a ceiling visible and usually in reach, Boone Avenue is never less than twenty feet high and usually thirty or forty feet, with a few places the ceiling is sixty feet above the floor.

Remember way back when I mentioned that there are places you can see the sandstone cap over the cave? Places that would be open river in any normal limestone formation? Well, Boone Avenue is one of them for most of its length. The ceiling is flat sandstone; the walls and floor are water-sculpted limestone. You're walking at the bottom of a weird ravine with a roof where the sky should be.

It wiggles all over -- both side to side and up and down. We usually couldn't see most of the tour group; typical visibility would be maybe eight feet in either direction.

Boone Avenue is well over a mile long, which I should have mentioned; it may be more than two. There are wide places as well as narrow -- one spectacular one included bats and cave crickets (we were a bit startled to see bats flying about during the day, and so far into the cave; a ranger said that we weren't all that far from one of the twenty-three cave entrances -- a small, winding, mostly-vertical one). Another wide spot had a waterfall -- not a solid stream like an above-ground waterfall, but more like a shower spilling out of the sandstone, and then vanishing down into a pit that, cliche though it may be, looked bottomless. It went down at least another sixty feet from our own 250-foot depth.

We passed a couple of side-passages, one of them very large; Kiri wanted to explore them all, but we stayed on our own path.

The floor in Cleveland Avenue had been largely level; the floor in Boone Avenue was anything but, with steep slopes, sudden drops, and so on, and the wide areas were usually much deeper on one side than the other. Lots of rubble.

We passed a couple of limestone formations -- but obviously dead ones. Live formations, even if not perceptibly wet, have a warm sheen to them that makes them almost seem to glow in the light; dead ones are just lifeless rock, gray and dusty. There were no live ones in Boone Avenue.

Boone Avenue looked much more like a cave than Cleveland Avenue; no one could ever mistake it for a subway tunnel.

It eventually widens out more or less permanently -- and that's where you start to find "break-down mountains." These are places where the ceiling fell in -- not enough to make a hole all the way to the surface, but a lot.

The first and tallest is called Mt. McKinley, and we got to climb up ninety feet of steep mud; there are hand-rails, and you need them.

The second set of rest rooms is on top of Mt. McKinley, though, along with water fountains and benches, and we took a break there.

At Mt. McKinley the passage was about thirty feet wide and a hundred feet high -- at the bottom; at the top, if I stood on a bench, I could touch the ceiling, I'm pretty sure. (I didn't try.) Pipes had been sunk through the sandstone for the plumbing, and the holes then cemented up.

In order to get up the slope, the trail zigzags back and forth, by the way -- not just on McKinley, but on all the break-down mountains. There are four on that route.

After McKinley the character of the passage changed; it stayed wide and relatively straight, rather than narrowing back down. The walls were no longer so clearly layered or obviously water-shaped. Frankly, I found this part to be much less fun, and that wasn't just because I got tired of climbing up and down.

On the last break-down mountain -- if it has a name, no one told us -- we paused, regrouped, and got a demonstration of utter darkness. Also a look at what the cave looked like by flashlight, by torchlight, by lantern light.

And that brought us to the end of Boone Avenue, and into a section of cave that defies adequate description. For the next half-mile or so we were going up and down stairs, through narrow little holes and big irregular rooms, and hither and yon. Some of this was slow going -- we apparently had at least one person who was either getting very tired or developing claustrophobia, as she would sort of freeze every so often, usually partway up or down a narrow staircase through a tight passage. She was, unfortunately, in front of us.

The rangers didn't have much to say here, because (a) there was nowhere they could come even close to collecting 120 people in one place, and (b) I don't think there's much to be said.

At last we climbed up a slope into a fairly wide area and found ourselves arriving at Frozen Niagara and the Drapery Room. Only 5% of Mammoth Cave has any sort of limestone formations, and this area is some of the best of that 5%. Frozen Niagara is a huge mass of flowstone -- the dimensions were given on a little sign, but I'm not sure I remember them right. 50 feet wide, 30 feet high, maybe? Something like that.

Do I need to explain what flowstone is? Stalactites, stalagmites, drapery, rimstone?

Frozen Niagara appears to have formed in a vertical shaft where something diverted most of the flow, so that there's still a large open space underneath the main mass of flowstone. That's the Drapery Room. It's a dead end, and the only way in or out is a staircase, forty-nine steps. They've put a railing down the middle of the stairs, so you go down one side and, when you're done, up the other; it takes awhile for 120 people to do this.

If you wanted to, you could skip the Drapery Room and wait at the top, but I don't think anyone did.

The Drapery Room is gorgeous and spectacular. It's maybe a dozen feet across at the bottom, twenty feet across midway up, and twenty-five feet high, at a guess. It's underneath Frozen Niagara, which kept the whole thing from filling in, but around Frozen Niagara the walls and ceiling are a maze of drapery and stalactites, a regular fairyland of translucent orange stone.

From there, the tour sort of fell apart, as people trailed on out through the last fifty yards or so at their own pace and boarded the waiting buses. When the kids felt the warmer air they began hurrying us along, eager to be done -- which is a shame, because that last passageway is actually full of nifty stuff. When you come up out of the Drapery Room you follow a curve around to the left, and through an opening into this final passage, and when you reach it, there on your left is another vertical shaft, like the one that became the Drapery Room. This one, however, has no formations in it, and drops straight down a hundred feet or so to Crystal Lake, the widest, stillest part of the Echo River, somewhere down on the fourth or fifth level.

From there the passage is fairly level and fairly straight, and it emerges from a hillside. To either side of the path are various formations, some of them impressive, some very delicate -- there's some nice rimstone. There's fencing protecting some of them; that, combined with the lighting and the way columns and walls and the shape of the tunnel subdivide things, makes it seem almost as if you're walking past dioramas rather than through a cave.

And then we were out, blinking in the sunlight and sweltering in the heat -- there's a roof over the path to the parking lot to ease the adjustment, but it was still a shock.

We boarded the bus to ride back to the Visitor Center. The skies were looking threatening -- thunderstorms were predicted, but hadn't yet arrived. Except that it began sprinkling as we rode. Then raining harder, and harder...

By the time we got out of the bus and under the overhang at the Visitor Center it was really starting to pour, a great soaking torrent -- and our car was at the far side of the parking lot.

We dashed across to the gift shop, hoping that the rain might let up -- but it just got harder and harder, so after a few minutes I went to get the car and bring it around to the gift shop door. No point in all of us getting soaked.

By the time I pulled up at the door the parking lot was awash in about two inches of water, and it was coming down harder than ever. Everyone bundled into the car as quickly as possible, and we headed out, bound for Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.

Visibility sucked getting out of the park and onto the Interstate, but it did let up somewhat not long after, and by the time we got onto the Cumberland Parkway eastbound it was still raining, but it was no longer a real downpour.

From Mammoth Cave to Pigeon Forge is 260 miles, and we were only getting started after the tour, which meant about 4:00 in the afternoon, so we didn't think we wanted to go that far. What we'd planned on was camping at the Cumberland Falls State Park, in the middle of nowhere on the Kentucky side of the Kentucky-Tennessee line, and going on to Pigeon Forge in the morning... but camping in the rain doesn't really appeal, y'know? So the theory was we'd drive until we got tired and/or grumpy, then find a motel.

We made pretty good time, actually. Better than I expected. We got onto I-75 and into Tennessee before even seriously considering stopping.

The rain stopped just before we got off the Cumberland Parkway, by the way -- we'd finally outrun the storm after three hours of rain.

Julie started pointing out motels somewhere north of Knoxville; in retrospect we probably should have stopped, but I wanted to get past Knoxville, I'm not sure why. We took the northeastern bypass and got onto I-40 eastbound, and I was ready to look for a motel -- and there weren't any. Of course.

We got to our exit -- Exit 407 -- and turned off, and headed south into Sevierville, and finally started seeing motels again. We stopped and inquired about prices at a couple, and finally wound up at a decent all-suites place. Weekdays, a suite was $49, which was what we paid -- but we heard someone else making reservations for a weekend. It's $69 for Friday, $89 for Saturday.

We'd promised Kiri we'd buy her fireworks somewhere along the way -- they're illegal in Maryland, but we like 'em, and they're all over in Tennessee. We'd gone past several places that sold them, but didn't stop because we wanted to find a place to stay.

Naturally, we didn't see another one from the motel to the Tennessee state line... but I'm getting ahead of myself.

I didn't mention that by the time we stopped the kids were being so grouchy and unreasonable that we actually put 'em back in the car and pulled out of the suites motel and headed on down the road rather than try to settle an argument over who would sleep where. When the next place cost almost twice as much, and they'd had time to calm down, we went back.

And one reason we didn't really have much trouble over sleeping arrangements on this trip is that Julian never did really snore. One night, out of eight or however many it was, he did make some odd little noises, but he seems to have finally outgrown his ghastly wheezing and groaning.

Which wasn't his fault in the first place; he was born with a defect in his soft palate. Caused a speech impediment, which he's mostly grown out of as well, and necessitated some weird orthodonture, but the snoring was the most spectacular effect. At its peak we could hear it from across the hall, through two closed doors. It hasn't been that bad in years. It's good to think it may be gone entirely.

"The Parkway," as it's known, is the highway running from I-40 to Gatlinburg. Gatlinburg is the main entry point to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Gatlinburg is actually in the foothills. Just north of it is Pigeon Forge, which is on the flat. North of Pigeon Forge is Sevierville. North of Sevierville is Exit 407 off I-40.

We visited the Great Smokies many years ago, when we lived in Kentucky. We drove through Sevierville without even noticing it -- the parkway doesn't go through the center. At the time Pigeon Forge consisted of the parkway and a few little side-roads; the parkway was lined with cheap motels, and the two things to see there were the old mill on the Pigeon River (yes, that's where Pigeon Forge got its name -- there was a smithy by the river there) and Silver Dollar City, an Old-West-themed amusement park.

That was it. Pigeon Forge, such as it was, existed for tourists only as overflow housing for Gatlinburg and the National Park prior to the construction of Silver Dollar City, and Silver Dollar City was never all that successful.

In fact, in the early 1980s Silver Dollar City was put up for sale.

And it found a buyer, a local girl, born and raised in Sevierville and looking for an investment that might help her hometown -- Dolly Parton.

She renamed it Dollywood and re-themed it from Old West to country and western, and built a huge restaurant-music hall on the parkway right by the turn-off for the amusement park.

Thus was Pigeon Forge reborn.

Dollywood was, and is, successful, and it's drawn in lots of other attractions. The battered old motels have been refurbished or replaced (I did spot the one we'd stayed in). Restaurants have blossomed. There are several theaters and music halls, a water park, kitschy little museums (no less than three car museums!), and so on. Dolly's own music hall, the Dixie Stampede, is the biggest and best of 'em, but the Laura Mandrell that's due to open soon may give it competition...

This is all tacky stuff, the sort of thing it's very easy to make fun of -- especially if, like us, you aren't a country music fan. It's cheesy and kitschy and ugly.

On the other hand, it's sucked huge quantities of money into the area, and created a thriving economy in a town that was something of a dump. It's spilled over into Sevierville -- the motels and tourist traps now start pretty much as soon as you get off I-40 now, where that used to be lined with decaying farmsteads.

The locals appreciate it, too. Sevierville has renamed its main drag Dolly Parton Boulevard, and a statue of Dolly stands in front of the Sevier County courthouse, according to the map -- we didn't go to see for ourselves. She's the local hero, big-time.

It used to be Gatlinburg that was the big draw -- especially in winter, since decent skiing is scarce in the south and Ober Gatlinburg is about the best you'll find. Now Gatlinburg looks a bit tatty by comparison, and Pigeon Forge is booming.

And the locals we saw, while they're still working in motels and pancake houses, look a lot happier than I remember them. Money can do that.

So we woke up in our suite in Sevierville to a grey, dreary day, and cruised down the parkway to the International House of Pancakes for breakfast. We ate breakfast, discussing plans for the day -- the weather was somewhat unsettled, which made planning difficult. The kids wanted to go to the water park, Julie wanted to hike in the National Park, I really didn't have anything in mind.

Then it started raining. Sigh.

Water parks don't work very well in the rain. Neither does hiking.

The National Park has "motor trails," however, so we decided to drive one of those -- the Roaring Fork Motor Trail. Roaring Fork, Tennessee was a miserable, hardscrabble farming community that made pre-Dolly Pigeon Forge look like heaven on Earth; the National Park bought it in the 1930s and relocated the inhabitants to Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, and Sevierville. Most of them were bright enough to use the money they got for their land to go into some business other than farming, and you'll find their descendants all over the place, running motels and fast-food joints -- many of the names that turn up over and over on businesses in Pigeon Forge, such as Ogle, are mostly former Roaring Fork families.

The name "Roaring Fork" comes from the stream -- it's too small to really call it a river -- that ran through the community; it's loud. It bounces down the mountainside.

By the time we'd actually gotten onto the motor trail and covered the first half-mile or so the rain had stopped again -- it never amounted to much -- so we made stops along the way, getting out to admire the scenery and taking a foot trail up to Grotto Falls. The first part of the motor trail is devoted to the forest, the second half to the former town of Roaring Fork.

(To give you an idea what Roaring Fork was like -- the Clampetts would've been right at home. No plumbing, no electricity, no paved roads, most families living in one- or two-room cabins. One such cabin, which was home to husband, wife, and nine kids, is still there as an exhibit. Two rooms that together are smaller than a one-car garage.)

The forest is beautiful. It's all secondary growth, still far short of climax forest, but it's lovely. There are rhododendrons everywhere, and hemlock -- the locals allegedly called them spruces, and there are place names based on that, but they're hemlocks. It's rocky, but less so than, say, New England. The hike up to Grotto Falls is somewhere between a mile and a mile and a half, and was well worth the walk.

Grotto Falls itself is almost too picturesque to believe -- water pouring over a rocky overhang, just high enough that you can walk behind the falls without stooping, into a rock-strewn pool.

The original forest, before it was cleared, was mostly chestnut, but the chestnuts were wiped out by blight. There are still chestnut logs and stumps scattered about; a ranger told us that some of the roots are still alive, and every so often a new shoot will grow -- and then die of blight. It's sad.

That was the morning; we went back to Pigeon Forge for lunch (because we couldn't find anywhere to park in Gatlinburg), then decided to head on through the park to North Carolina.

(The main road between North Carolina and Tennessee is I-40, by the way. I-40 was closed by a rockslide in late June, and still hadn't reopened; it was apparently a very bad slide. I don't know whether it's open now or not. Truck traffic isn't allowed through the park, but I suspect that there were lots of cars taking that road not to see the mountains, but just to get across.)

The main road through the middle of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park runs from Gatlinburg, TN through Newfound Gap to Cherokee, NC. We drove it at a fairly easy pace, stopping every so often to admire the view and making a side-trip along the ridgetop to Clingman's Dome... well, almost; we actually turned back before reaching the observation tower, as we decided we'd seen enough scenery for the moment.

The Smokies are named that for the mists that drift across them; the forest there puts enough moisture into the air that except on the very driest of days there are clouds obscuring patches of treetops. It does look like smoke -- not the thick, dark smoke of a forest fire, but pale, wispy smoke.

It's very beautiful. Standing atop the highest ridge (which is the state line between Tennessee and North Carolina) and looking out over mountainsides completely covered in lush forest and partially veiled in mist, and beyond them are more mountains and mist, and beyond that still more, fading into the distance... well, it's gorgeous. My kids aren't particularly impressed by scenery, but even they admitted the view was really neat.

Eventually, though, we drove back down into the world again, and emerged in Cherokee -- which is on the Cherokee reservation; the name isn't just an empty historical reference.

Cherokee isn't as brash and lurid and noisy as Pigeon Forge, but it's no thing of beauty; the local economy relies heavily on selling junk to tourists. Kiri pointed out that she saw more advertisements offering mocassins for sale in any given mile of Cherokee than she'd seen in all the rest of her life prior to that, all put together.

It's also not as financially successful as Pigeon Forge; it's pretty down-at-the-heels. We did make one stop, at one of the nicer and newer souvenir shops, where we bought souvenir spoons for Maine, New Jersey, and Maryland -- it's a long story -- then turned north on a minor highway bearing a number I've forgotten, headed for I-40.

At this point we were looking for cheap lodging, somewhere between Cherokee and Asheville. I had a theory that there would be motels along I-40 desperate for business due to the highway closing, so we got to I-40 before we started looking. We got a pleasant dinner at a steakhouse at one exit, and then asked prices at the two motels at that exit... and decided that however sound our theory might have appeared, it was disproven by the empirical results. The motels were not cheap at all.

I then came up with the clever idea of maybe taking the old Asheville highway that I-40 had replaced, in hopes of finding something there. We got lost making the transition to the desired road (it has three route numbers; I think one of them was 19), but at last found it and headed east, and sure enough, found a motel that cut us a good deal on two connecting rooms. This motel was the Asheville Days Inn West, which is not in Asheville; that it's survived on the old road is because it's near where the old road intersects I-40, and it's at least sort of close to Asheville. We got two rooms and breakfast for $79, which seemed fair.

The management told us that the closure of I-40 had wiped out most of their business for two months of what's ordinarily their peak season; they were hurting. And in fact, the place was mostly empty; I don't think a single room on the third floor (of three) was occupied, and the second floor was sparse.

Good clean rooms, good beds, nice pool... lousy ventilation. The rooms were so stuffy we had to keep the air conditioners going just to have air fit to breathe, quite aside from temperature.

But other than that it was nice, and we had a pleasant low-key evening.

We got up Thursday morning, loaded up the car, and headed on into Asheville to see Biltmore House. This was our last scheduled tourist attraction of the trip.

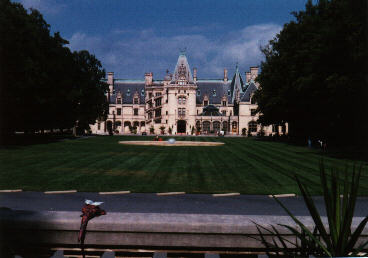

Biltmore House is the mansion that George Vanderbilt had constructed for himself; he started on it in 1889, and moved in for Christmas, 1895. It's the largest private home in America -- and it is still a private home, technically; the Vanderbilts (well, their descendants through the female line) still own it. They only live there one day a year -- the family still holds their Christmas party there, as they have every year since the 1895 housewarming.

The rest of the year it's open to tours.

Julie and I had been there before; the kids hadn't. Neither had McGillicuddy, my stuffed dragon, who was along on the trip, and we decided that Gilli would want to see the closest thing to a real American castle we were ever likely to find, so we stuck Gilli in a tote bag (with the camera and guidebook) and brought him with us.

In order to build the place, George Vanderbilt first had to build a railroad to bring in materials, and a village for his workers to live in. He acquired a huge tract of land -- 135,000 acres, I think -- most of which is now the Mt. Pisgah National Forest; the family only owns (only!) 8,000 acres now. He intended to build a working, self-supporting estate -- wealthy Americans have been trying for this for centuries, as demonstrated by Mount Vernon, Montpelier, and Monticello -- but it rarely comes off; Biltmore has had a dairy ever since it was built, and they've now added a winery, but I suspect the tours and restaurants still make more money.

And the estate as a whole still isn't self-supporting.

You've probably seen pictures of the house; it turns up all over. It's in the style of a French chateau. Having toured the Loire chateaux long ago, though, I can say that Biltmore's an improvement on its model in many ways.

The front lawn is long and elegant, and extends from the house to the vista. What's a vista? It's a structure (modeled after an Italian garden terrace) that exists almost entirely so you can stand on it and admire the house and lawn. (Here's a picture of Gilli doing just that.)

Since it was owner-occupied up to at least 1929, and is still in the original family, Biltmore still has the original furnishings; it's never been stripped, trashed, rebuilt, restored, or otherwise messed with. There are a few modern concessions, like reflective tape on stair edges and plexiglass over the ironwork on the elevator, to the needs of hordes of tourists, but it's mostly just what Vanderbilt built. I can't remember the architect's name (he was good!), but the landscape work was done by Frederick Olmstead, who designed Central Park.

So we drove in the gate, drove up a few miles, bought tickets, drove up to the parking lot, then walked up to the vista and got our first look at the place.

The kids were impressed. They've toured mansions before -- like Mount Vernon, Montpelier, and Monticello, among others -- but this one is something special.

I'm not going to describe it room by room. I'll note the winter garden is lovely, and the dining hall somewhat overdone (the banquet table seats 64). And I'll also note that it's a very well-designed place; everything's carefully thought out and tastefully decorated, and comfortable -- so often, with these grand old houses, one wonders how anyone could actually stand to live in them, but here that's not the case. It's very easy to imagine reading comfortably in the library, strolling along the terrace admiring the view of Mt. Pisgah, relaxing in the winter garden, playing in the indoor pool... it's no wonder the family's held onto it.

Often, when I tour old houses, I'll think a given room is ugly, or a set of furnishings mismatched, or some function badly arranged -- I note that another Vanderbilt, who owned Montpelier, was responsible for the single ugliest room of art deco I've ever seen -- but not at Biltmore. It's all gorgeous.

We toured the house, then got ice cream from one of the restaurants in the stable/carriage barn, then looked at the gift shop (where the music is provided not by Muzak, but by a $10,000 music box), then strolled through the gardens before heading back out through the estate to the village for a late lunch.

One interesting statistic: In 1895, Biltmore employed 250 people, a large percentage of them servants in the main house. The estate now employs 647 people, some of them descendants of the original 250.

I hadn't expected that the number would have gone up.

One final comment about the house: It's unusually open and airy for Victorian architecture, or any sort of grand old house; I think that's a major reason I like it so much.

(Gilli liked it, too.)

After lunch we headed up the road to an area fraught with furniture discount outlets -- we could use new kitchen chairs -- and looked around, but the best chairs we found were made in Pennsylvania, and we couldn't quite bring ourselves to buy chairs in North Carolina and drive them 300 miles home knowing that they were built less than 200 miles from our front door.

From there we called my sister Charlotte and her husband Mark. They'd agreed to put us up for a night -- we'd had them as guests at our place for a couple of days back in July.

It took three tries to find a working pay phone, and the number I had was out of date, but eventually we got hold of them and made the necessary arrangements (and got directions!) and headed on to Clemmons, just outside Winston-Salem.

We found Charlotte's place -- it's a tidy little ranch house at the end of a dead-end street in the back of a subdivision. Julie and I were assigned one side of the basement, Julian the other, and Kiri got the living room sofa.

Charlotte and Mark have two kids, Laura and Arthur. Laura's seven, I think -- about that, anyway -- and Arthur is, um... four? I forget.

However old he is, Arthur is remarkable because, as Kiri puts it, "He never shuts up!" He's the most talkative preschooler I have ever met in my life. Laura's very quiet; Arthur talks enough for both of them.

Charlotte's an assistant professor at Wake Forest -- in research, not teaching. (She has two doctorates, so this isn't a big surprise.)

Visiting there felt a bit odd, because Charlotte's got a significant fraction of the household furnishings that we grew up with -- it's strange to see these objects again in an unfamiliar setting, mixed in with unfamiliar stuff. She's got my father's old piano, for example (which is still in good shape but could stand tuning), and our old kitchen table, and assorted knicknacks (including some that were originally mine -- I remember buying them in Montreal in 1961, when Charlotte was just a baby).

I mentioned how peculiar it seemed, and she said that she understood perfectly, because she'd felt the same way visiting us -- we have the old card table and folding chairs, and Aunt Nora's cabinets, and so on.

Ruth and Marian have some of the old stuff, too, but I guess I'd gotten used to that.

Once we were settled in we phoned Julie's brother in Durham, and discovered there'd been a communications breakdown -- we'd been planning to head there from Winston-Salem, arriving Friday afternoon, but he was expecting us Saturday and had a date for Friday night.

We conferred. We decided we'd had enough traveling and wanted to get home, and would therefore head home from Winston-Salem -- but first we would check out Old Salem.

At least, Julie and I would; the kids were emphatically not interested.

So Friday morning after breakfast, Charlotte headed off to work, we set the kids up at the computer with a slew of video games (they got addicted to Rodent's Revenge, sufficiently that we now have copies on both desk machines here at home), and Mark drove us to Old Salem.

Salem was founded in the 17th century by Moravians who came down from Pennsylvania. Moravia is a place in what's now the Czech Republic -- it's the part of the CR that isn't Bohemia, pretty much -- but "Moravian" in this case refers to a particular Protestant sect that started in Moravia and spread first to Germany, then to the New World. It was one of these semi-communal theocracies that flourished in early 19th-century America -- everyone was classified into a "choir," each with its own set of rules. For example, the Widows' Choir wore white ribbons around their necks, while married women wore blue, etc.

The church still exists; the community structure is long gone.

Anyway, the Moravians from Pennsylvania occupied a big chunk of north-central North Carolina, naming their region Wachovia -- some of the church-spawned businesses still use the name. Salem was their central community. It was very modern for the time; George Washington toured it to get ideas for use at Mount Vernon and in the Federal City, and was very impressed with the plumbing. (They had running water.)

However, in the 19th century Salem's economy collapsed. The Moravians brought in non-Moravians (I don't know what the term is -- gentiles?) as hired labor, establishing them in an adjoining town called Winston, and eventually Winston effectively absorbed Salem, creating Winston-Salem.

Many of the original buildings survived, though, and they've now been restored as a museum, like Williamsburg or Sturbridge -- except they didn't need to actually rebuild anything the way Williamsburg and Sturbridge did.

We toured the bachelor hall (where older boys and unmarried men lived and worked) and a couple of houses, including the doctor's, which included his apothecary and an exhibit on just how horrific and primitive 18th-century medicine was.

We wound up at the bakery. The original bakery stayed in operation as a family business until after the First World War (I forget the exact date), and then served as an antique shop, and the antique shop's proprietor wasn't stupid enough to update anything or tear anything out, so when the museum was set up it was easy to re-open the bakery, using much of the original equipment. We bought bread and cookies -- delicious!

And then, after lunch with Mark, we headed home.

And that's it; end of trip report, finally.

Due to the length of this report, it was divided into two pages (not counting spin-offs). If you missed the first part, click here.

For those who somehow stumbled in here by accident -- hi! I'm Lawrence Watt-Evans. I'm the author of more than four dozen novels and well over a hundred short stories, as well as innumerable articles, comic scripts, poems, and other miscellany. This is my personal website, the Misenchanted Page; the name is a reference to my bestselling novel The Misenchanted Sword.

That's it; here's your list of handy exits:

The Misenchanted Page

Front Page | Main Site | E-mail me!