A Novel by Lawrence Watt-Evans

Book Two of War Surplus

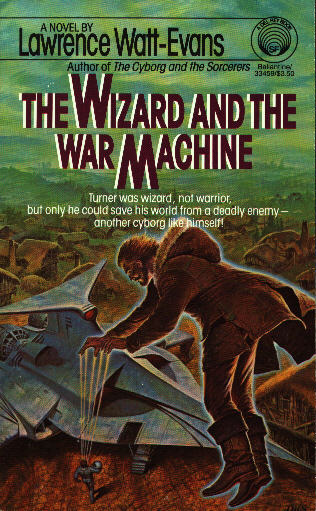

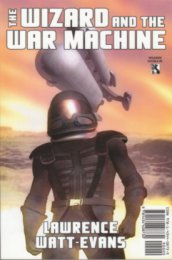

The Wizard and the War Machine is the sequel to The Cyborg and the Sorcerers. It was first published by Del Rey Books September 1987, ISBN 0-345-33459-0, with cover art by Darrell K. Sweet.

The Wizard and the War Machine is the sequel to The Cyborg and the Sorcerers. It was first published by Del Rey Books September 1987, ISBN 0-345-33459-0, with cover art by Darrell K. Sweet.

It was reissued as half of Wildside Double #5 in September 2010, and as an ebook in March, 2011.

At the end of The Cyborg and the Sorcerers, Sam Turner was making a life for himself on the planet Dest. He thought he had left the long-lost interstellar war between Earth and its rebellious colonies behind him forever.

"Forever" turned out to be eleven years. That was how long it took for another Independent Reconaissance Unit to respond to the distress call his ship had sent before it was destroyed.

And this one made his own berserk killer computer look sane.

The Wizard and the War Machine

by Lawrence Watt-Evans

Chapter One

Bright daylight spilled through the chunks of colored glass set into the windows, striping the fur carpets with bands of red and green and blue. The children were using the slowly-shifting streaks of colored light in a complicated game of their own devising; Sam Turner watched for a moment, standing in the kitchen doorway, but could make no sense of it. The only rule he could see was that when the daylight's movement caused any particular stripe to touch a new rug, everybody screamed with excitement and ran about wildly.

Perhaps, he thought with a smile, that was really the only rule there was.

Back on Old Earth or Mars the sun's movement would have been too slow to use in a children's game; even here on Dest, in the deep of winter when the elongated stripes made its motion more obvious, he was surprised to see it involved.

"Daddy!" little Zhrellia called, "Daddy, daddy, you play!"

He shook his head and said, "No, I don't know how. Besides, I should get to the market before all the good stuff is gone." He gestured at the folded linen sack he had tucked under one arm.

All three children expressed polite dismay, Zhrellia pouting, Debovar downcast, and Ket impassive; Ket added, "Will you bring us some honey? It was all gone at breakfast."

"I'll see." He smiled fondly. "You just go on with your game. If you need anything, shout; your mother will hear you."

He was lucky, he told himself as he crossed the room, to have three such children, all healthy, without a visible mutation amongst them. He was lucky to have the wife he did, and his position in the community. Most of all, he was lucky to be alive, after what he had been through in his younger days. Back then, when he was traveling through space with a bomb in his head, fighting a war that was long over under the direction of an irrational computer, he would never have believed he would someday have children and a comfortable home.

He paused at the threshold to wave a farewell, then stepped through the door to the little platform beyond, leaving the luxuries of his family's apartments behind.

Around him were four bare wooden walls, and two floors above him was a patchwork of metal, wood, and concrete that served as a ceiling. The wooden platform on which he stood was secured to only two of the walls, forming a triangle across one corner of the chamber. Other doors opened onto similar platforms from other walls and on other levels, but most of the area that should have been floor was simply open space over a hundred-meter drop.

He glanced over the edge, gathered his concentration, and stepped off.

At first he hung suspended in mid-air, but then he allowed himself to sink slowly but steadily downward.

He looked about casually, watching the walls slide up past him; the rusty, blast-twisted steel frame of the ancient skyscraper showed plainly through the cobbled-on walls of glass and wood. When he had first settled in Praunce, eleven years earlier, he had worried that the damaged metal structure might not be sound, that his cozy new home might someday fall, brought down by high winds or ground tremors, killing him in its collapse.

He smiled to himself at the memory.

Later, as an apprentice wizard, he had also been frightened by the necessity of levitating himself up and down the central shaft. His master, however, had insisted. Wizards lived in the towers; that was the way it was done in Praunce. It always had been the way, ever since the first wizard arrived there not long after the Bad Times, and it presumably always would be. As an apprentice, Turner had lived in his master Arrelis' tower, and he had levitated up and down the central shaft. Since he had by then already survived any number of things that should have killed him, he had ignored his nervousness.

Now a master wizard himself, albeit not a particularly good one, Turner knew that his fears for the building's safety had been groundless; he could perceive the strengths and weaknesses of the structure, could feel the stress upon it, and knew that despite rust, despite the damage done by the nuclear blast that had destroyed the city on whose ruins Praunce had been built, despite everything, the tower could easily stand for another century or two.

The drop down the shaft, however, still worried him on occasion, and when his children had been younger the thought that one of them might somehow open a wrong door and fall off the platform had terrified him. Even now, at times, he still worried about Zhrellia, despite locks and warnings. Like any two-year-old, she had more curiosity than caution.

He smiled anew when he thought of her.

He looked down; he had made more than half the descent. He could see clearly, despite the dim light and drifting dust, the stacked sacks of grain that covered the floor to a depth of a dozen meters or so. The piles had been shrinking since the onset of winter, but they were still substantial. The city was well-supplied this year, as it usually was.

He sneezed, and fell a meter or so before he caught himself. The dust had tickled his nose. The hollow centers of the towers were always drab and dirty, because nobody could be bothered to clean them; the stored grain inevitably left behind dust and grit that drifted about and slowly encrusted every surface, including, whenever he passed through, his skin and the inside of his nose.

At least, he thought, it was reasonably warm in here. He could have gone out a window and down the outside of the building, but the outside air was freezing cold, and as a wizard he was expected to generate his own heat-field rather than wear a coat -- it helped maintain the impression that wizards were not subject to the weaknesses that troubled lesser breeds of humanity.

Generating heat could get tiring, though; better to put up with a little dirt than to exhaust himself for no reason, he told himself as he settled onto the trap door that led into the tower's eight lowest floors. Ordinary men and women lived in the base of the tower -- along with a good many mutants, sports, and other non-ordinary men and women, most of them the result of the lingering radiation and chemical contamination in the area.

No wizards lived below him, though. Wizards, and only wizards and their families, lived in the tops of the towers. The rest of the populace stayed close to the ground. Even after eleven years, Turner had not quite decided whether he approved of this division between the city's elite and the common masses. It was certainly undemocratic, and Turner's parents had brought him up as a believer in democracy, but on the other hand, wizards really were different from other people, and to pretend otherwise would be hypocritical.

Besides, the wizardly elite was by no means a closed society. Anyone could apply for an apprenticeship and stand a reasonable chance of being accepted, and virtually every apprentice became a wizard, and all wizards were accepted as equals, regardless of whether they had been born to princes, peasants, or even other wizards. Minor distinctions might be made on the basis of seniority or ability, but never on the basis of birth. Turner himself, after all, had been as complete an outsider as anyone might imagine, and yet he had been fully accepted.

Few people did apply for apprenticeships, though, which puzzled him. He preferred to attribute it to a combination of laziness and mistrust. Wizardry was mysterious, Turner thought, and probably looked a good bit harder than it actually was.

Actually, though, he reluctantly admitted to himself that the wizards discouraged would-be apprentices. Apprentices meant work and responsibility, and more wizards meant a wider distribution of the powers and privileges they enjoyed.

But anyone could apply. Turner soothed his egalitarian instincts with that reminder.

He opened the trap door without touching it, lifting himself up out of the way as it swung back. When it had fallen back as far as the hinges would allow he let himself sink slowly downward through the opening.

He paused a few centimeters off the floor of the corridor below the trap, aware of an odd, unfamiliar sensation, the sort of sensation that he would once have described as "feeling as if he were being watched." Oddly, the phrase came to him in his native tongue, rather than the Prauncer dialect of Anglo-Spanish that he had spoken and thought in for the past decade.

Nobody, though, should be able to watch an alert wizard without the wizard knowing it. Turner had accepted that as fact for several years now. He rotated slowly in mid- air, looking with both his eyes and his psychic senses, but could neither see nor feel anyone paying any attention to him. A few people were in the rooms along the corridor, behind their closed doors, but none showed any sign that they were aware of his presence. He sensed their auras as calm and blue.

With the mental equivalent of a shrug he dropped to the floor and began walking toward the stairs. He was imagining things, he told himself; either that, or some of the circuitry in his body was acting up. Perhaps some obscure component, a chip or a bit of wiring somewhere inside him, was reacting to static electricity built up in the cold air, or to sunspots -- or starspots, if that was the word, since Dest's primary was not Old Earth's sun. Perhaps, he theorized, some mechanism in his body was breaking down from age and lack of maintenance and disturbing the equilibrium of his senses.

The latter was not a particularly pleasant possibility to dwell on, with all it implied for future breakdowns. He pushed it aside.

He was halfway down the second flight when he again thought he sensed something; this time it seemed to be a sound he didn't quite hear. He slowed his pace, and paused at the bottom of the staircase, listening intently.

His ears caught nothing but the distant sounds of the city going about its business. His psychic senses detected nothing but casual disinterest. Nonetheless, he was uneasily certain that he did hear something -- he knew he did. He tried to remember how to listen to the electronics wired into his nervous system, but it had been so long that he struggled for several seconds before he again picked up a faint tremor of something.

He concentrated, willed himself to hear it, and began to pick up something, too faint to be considered a sound, but with a distinct rhythm. He recognized it as speech, but the rhythm did not fit any dialect he had heard on Dest.

It did, however, fit Old Earth's polyglot common language, the language used in government, trade, and the military, the language he had, as the child of a bureaucrat and a corporate executive in urban North America, spoken as his own until reaching Praunce. The mysterious speech fit the rhythms of polyglot, and it was growing steadily louder and clearer.

"Oh, my God," Slant said aloud in his childhood tongue, the years of practice in using Prauncer terms, swearing by the three Prauncer gods, forgotten for the moment. He could make out the words now. He stood motionless in the corridor at the foot of the stairs, staring at nothing and listening to the barely-audible voice in his head endlessly repeating in his native language, in a distant monotone, [...Anyone loyal to Old Earth, please respond. Anyone loyal to Old Earth, please respond. Anyone loyal to Old Earth, please respond...]

[I'm here!] he shouted silently, reacting automatically, without any thought of what it might mean, [I'm here!]

- The Story Behind the Story:

In those quaint days of the early 1980s, when I wasn't online yet, I wrote a lot of letters. I got fan mail sometimes -- actual streetmail letters, with envelopes and stamps -- and I answered pretty much all of it. Some fans would then respond to my reply, and I sometimes found myself carrying on pretty extensive correspondence with them.

One of those fans was a woman in Tennessee who thought The Cyborg and the Sorcerers was the best thing I'd written, and that I ought to write a sequel.

I had no intention of writing a sequel. I thought the story was over; in fact, in the first version of The Cyborg and the Sorcerers that I'd submitted to my editor, Judy-Lynn del Rey, I'd left it ambiguous whether or not my hero even survived. Judy-Lynn made me change that; she called it a "reader cheater." Thanks to her, it would be possible to write a sequel, but I still had no plans to do so.

I'd plotted a couple of other stories in the same universe, actually, which I still haven't written all these many years later, but no direct sequel.

My fan in Tennessee wasn't having that, though. She wanted a sequel, dammit!

So I told her, "Look, the book didn't actually do that well. Sales don't justify a sequel." Which was debateable, actually, but mostly I was just trying to get her to drop the idea.

"How well would it need to sell to justify a sequel?" she asked.

"If it earns ten grand in royalties," I said, "I'll see if Del Rey wants me to write a sequel." I thought that was safe; at the time nothing I'd written had earned that much.

Ha.

"It's a bet," she said.

In August 1985 the royalty statement for The Cyborg and the Sorcerers showed earnings of $10,088.67 on 68,004 copies sold.

I like to think I'm a man of my word, so I conceded defeat. I sat down, worked out a reasonable plot -- that distress call Slant had sent out in the first book was an obvious hook to hang one on -- and sent Judy-Lynn del Rey a proposal for a sequel. I gave it a modified version of an alternate title for the first book; Judy-Lynn and I had argued a lot about the title, and only after it went to press did we agree that The Wizards and the War Machine would have been a better title. I dropped the plural, and put that title on the sequel.

I half-expected, and half-hoped, that she'd turn the proposal down.

She didn't. She sent me a contract.

And then she had a stroke, went into a coma, and never woke up. She died in February 1986, after being unconscious for months.

Meanwhile, I was busy writing The Wizard and the War Machine, and also relocating (my wife had been transferred from Kentucky to Maryland) and parenting (our second child was born in June 1986). It never occurred to me to talk to anyone at Del Rey.

I delivered the novel to my new editor in the summer of 1986. Her reaction was, "What the hell is this?" There was no record anywhere in the editorial offices that I was writing a sequel to The Cyborg and the Sorcerers. When they checked the contracts office, sure enough, there were the signed contracts, but no one in editorial knew anything about it. Apparently Judy-Lynn hadn't yet made any mention of it when she had her stroke.

But the contracts were in order, so she read the manuscript, and sent me the single most useless revision letter I've ever encountered. It more or less came down to, "This doesn't work. I don't know what's wrong with it, but it doesn't work. Fix it."

So I rewrote the entire thing, very quickly, and delivered it again, and this time she was ready and waiting, and from there on everything went smoothly. Not necessarily well, as I consider this one of the worst covers I've ever had, but smoothly.

And I was fired up with the whole idea of making this into a series. I proposed a third one, The Exile and the Empire.

Then the early sales figures for The Wizard and the War Machine came in. It sold roughly half as well as the first one. That was still respectable, but not good, so Del Rey didn't want a third one, for fear it would only sell half what the second one did.

So there are still only the two.

So far.

Publishing history:

North America:- First U.S. printing: September 1987, ISBN 0-345-33459-0

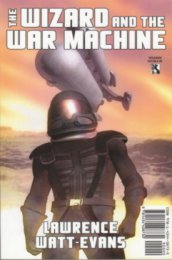

- As half of Wildside Double #5: September 2010, ISBN 978-1434408730

- As a Wildside ebook: March 2011

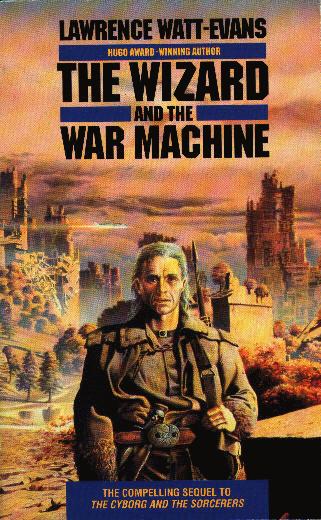

- Grafton edition 1990, ISBN 0-586-20750-3, with cover illustration by Geoff Taylor.

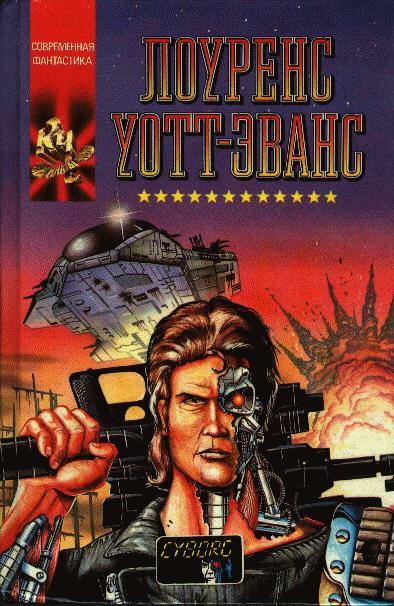

- Russian edition 1995, published by AST in an omnibus with The Cyborg and the Sorcerers in the Koordinaty Chudes ("Coordinates of Wonder") series. Russian title, Kiborg i Charodei. Translated by A. Komarinets. ISBN 5-88196-324-5.

Here are the covers of every edition published to date. Click on an image to see it full-size.

Wildside cover

(This is an omnibus edition with the first novel, The Cyborg and the Sorcerers.)

Russian cover

(This is also an omnibus edition with the first novel, The Cyborg and the Sorcerers.)

The Wildside Double #5 omnibus should be fairly easy to find, but here are a few places that have it:

And the ebook is available:

That's it; here's your list of handy exits:

The Misenchanted Page

Front Page | Main Site | E-mail me!