[An article commissioned by The Scream Factory: a brief history of pre-Comics Code horror comics other than E.C. It was removed from this site for a couple of years due to a reprint sale, but it's back now. It was published in Alter Ego #97, and was also used, in revised form, as the introduction for PS Publishing's collection of The Thing.]

When I was a kid in the 1960s, most of the comics I read had this little white seal on them that said, "Approved by the Comics Code Authority." Dell and Gold Key comics didn't have it, but DC and Marvel and ACG all did. I didn't know what it meant; no one I knew knew what it meant. It was just there.

When I was a kid in the 1960s, most of the comics I read had this little white seal on them that said, "Approved by the Comics Code Authority." Dell and Gold Key comics didn't have it, but DC and Marvel and ACG all did. I didn't know what it meant; no one I knew knew what it meant. It was just there.

I missed this first clue entirely.

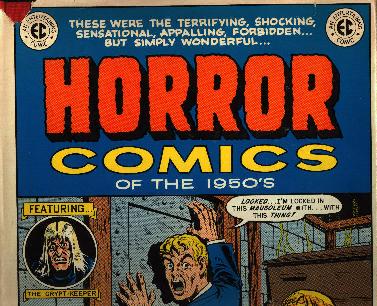

When I was a teenager, I came across a book in a store in Cambridge, Massachusetts -- a great big book, just out from Nostalgia Press. (Too big to fit the entire thing in my flatbed scanner, in fact.) On the front cover was the title Horror Comics of the 1950's. (On the spine it said "The EC Horror Library of the 1950's," instead -- I don't know why.) It looked pretty nifty; the cover art showed a man locked in a mausoleum where a rotting corpse was climbing out of its coffin. I opened it to the title page and read, "Those were the terrifying, shocking, sensational, appalling, forbidden... but simply wonderful HORROR COMICS OF THE 1950'S."

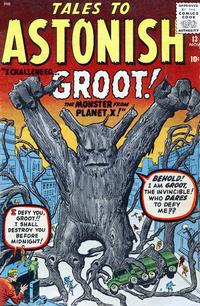

I had no idea what it was talking about. Horror comics? All I knew about were the mystery comics like House of Mystery, or the monster comics like Tales to Astonish before the superheroes took over. (I'd really liked Tales to Astonish, though; #13, the first monster comic I ever read, gave me nightmares. I liked that one a lot.)

I had no idea what it was talking about. Horror comics? All I knew about were the mystery comics like House of Mystery, or the monster comics like Tales to Astonish before the superheroes took over. (I'd really liked Tales to Astonish, though; #13, the first monster comic I ever read, gave me nightmares. I liked that one a lot.)

That was my second clue to the existence of a whole lost era in comics history.

The book was $19.95. I had maybe five bucks on me at the time, and I wasn't that interested in old comics at that point anyway -- I liked Kirby's Fourth World and Marvel's Conan, but I wasn't a collector yet. I didn't buy it.

But a couple of years later, when the Nostalgia Press volume was out of print, I was a collector -- my interest in completing my run of Conan the Barbarian had led to other things, I'd picked up a couple of Golden Age books at flea markets, and now I wanted to know more about comics history. Among other things, I wanted to know what had come between the Golden Age in the 1940s and the Silver Age in the 1960s.

So I picked up All in Color for a Dime and The Comic-Book Book

, both edited by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson, and I got Les Daniels' Comix: a History of Comic Books in America

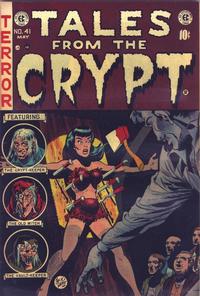

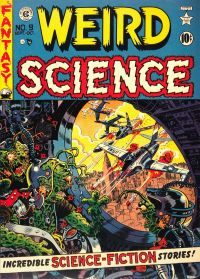

, and I found a few other books and articles here and there, and I learned about the legendary E.C. comics. All the experts talked about how wonderful E.C. was in its prime, how great it was to buy Tales from the Crypt or Haunt of Fear or Weird Science off the newsstand for a dime. I realized that this was what had been in that big book I couldn't afford -- E.C. stories.

But... but... had all the horror comics of the 1950s been published by E.C.? Those were the only ones anyone talked about, but surely there had been others?

In "The Spawn of the Son of M.C. Gaines," Don Thompson's chapter on E.C. in The Comic Book Book, E.C.'s competitors get one paragraph:

- "I searched newsstands. I bought some godawful horror comics, the kind that blazoned on the cover: "We dare you to read these stories!" They were nauseating -- dealing in things like giant crabs stripping bodies until they looked like the diagrams of human musculature you see in the encyclopedia, and mummies that sucked the guts out of people through their mouths (sorry to share that latter memory with you but I've been stuck with it for 20 years and maybe this will unload it) -- nauseating but not frightening. I must have bought a couple dozen of these things, all of them dreadful."

That was the longest mention of other horror comics I found anywhere; most writers dismissed them all as sleazy imitations of E.C. The accepted wisdom was that Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, inspired by radio suspense shows like "Lights Out," had invented horror comics out of whole cloth in 1950; that E.C.'s three horror titles had been immediate roaring successes so big that everyone else had slavishly but ineptly imitated them; that the entire censorship flap of the early 1950s, led by Dr. Frederic Wertham, was aimed at E.C.; that the Comics Code, the comics industry's self-censorship mechanism introduced in the fall of 1954, had been specifically designed to kill E.C.

That still seems to be the accepted wisdom.

There's just one problem. It's not true.

It took me awhile to realize this, but it eventually sank in, as I collected horror comics of all sorts and continued to study their history, that none of that was exactly what happened. The problem was that all the history had been written by E.C. fans; every single author who had published anything about the horror comics of the 1950s had been a devoted acolyte of William M. Gaines, and accepted what Gaines said as the true history of horror comics. Which it wasn't, quite.

I don't blame Gaines; he told his story as he remembered it. He was, however, biased, since he'd seen everything from the point of view of E.C.'s publisher. And he'd never bothered to study up on any of this; after all, he'd been there, he'd seen it first-hand.

Ask any cop about how reliable eyewitness accounts are. Especially a decade or more after the fact.

So here's what did happen, as I've pieced it together through twenty years of collecting horror comics and reading everything about them that I could get my hands on.

Comic books started out in 1933 with humor and adventure strips. In 1936 the first single-genre comics appeared, featuring detective stories. In 1938 came the superheroes. True crime arrived in 1942. By then there were hundreds of titles being published, and dozens of publishers, so a lot of experimentation was going on; superheroes and detectives still dominated the scene, but there were funny animals, humor strips, straight adventure, jungle stories, science fiction, and any number of other genres represented. Comic books were clearly taking a great deal of their inspiration from the pulp magazines; generally, if something sold well in the pulps, it would turn up in comics not long after.

Comics were surprisingly slow to pick up on two categories from the pulps, though. One was romance, which eventually arrived on the four-color page in the late forties; the other was "weird menace," which we would now call "horror."

Actually, "weird menace" was a particular sort of formula horror, featured in pulps such as Terror Tales, Horror Stories, and Dime Mystery, where some unearthly menace would threaten pretty women before being defeated and revealed to not be supernatural after all. Since it had a very definite element of sexual sadism, perhaps it isn't too surprising that it didn't make the jump to comics. Comics were for kids.

Actually, "weird menace" was a particular sort of formula horror, featured in pulps such as Terror Tales, Horror Stories, and Dime Mystery, where some unearthly menace would threaten pretty women before being defeated and revealed to not be supernatural after all. Since it had a very definite element of sexual sadism, perhaps it isn't too surprising that it didn't make the jump to comics. Comics were for kids.

There don't seem to have been any pulps that featured just plain horror stories as their only fare; besides the "weird menace" titles there was Weird Tales, but Weird Tales carried as much fantasy as horror.

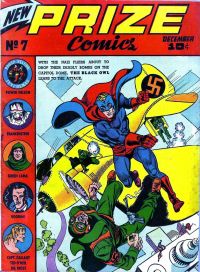

At any rate, there were no horror comics as such in the earliest days. The first real horror series seems to have been the "Frankenstein" series by Dick Briefer, in Prize Comics; it began in #7, dated December 1940, and ran until the title was cancelled in 1948. Prize Comics was a superhero title, featuring the Black Owl, the Green Lama, and the like, except for this one aberration.

"Frankenstein" didn't stay unique, though. No, no other horror strips were added; instead, Frankenstein changed premise. The monster was turned into a good guy, and became a superhero, fighting the Nazis.

And then, as World War II neared its end, superheroes began to go out of style, and Prize Comics gradually replaced its heroes with humor strips.

Frankenstein wasn't replaced; the feature was converted to a comedy, which it remained from 1945 until 1952. It was successful enough that Frankenstein Comics began in 1945, and outlasted the original Prize Comics.

So much, it would seem, for horror comics.

In late 1943 it looked as if horror might have another chance. An outfit called Et-Es-Go, which later became Continental Magazines, put out Suspense Comics #1, featuring the Grey Mask and other detective heroes. In the course of twelve quarterly issues Suspense Comics worked in a good many horrific images and stories; most of the covers didn't show the usual hero fare, but instead depicted horror imagery such as spiders, eyeballs, devils, etc.

In September 1944 someone named E. Levy started a superhero title called Yellowjacket Comics; in the course of ten issues and two years it switched ownership twice, first to Frank Comunale, and then to Charlton Comics.

It also ran horror stories as a back-up feature in eight of those ten issues, skipping only #2 and #5. These weren't borderline stuff; they were labeled "Tales of Terror," and narrated by an old witch. Two of them adapted classic stories by Edgar Allen Poe.

It wasn't exactly a horror comic, but it was a horror feature, very definitely. And it had the old witch narrator that Bill Gaines later claimed to have introduced to comics -- though it may well be that both Levy and Gaines were simply swiping from the same source, the radio show "The Witch's Tales."

In 1945 Rural Home Publications (an established comics publisher at the time) put out two issues of Mask Comics, which looked like a horror comic. The covers, by L. B. Cole, were certainly horrific enough -- one depicted moth people being lured by a candle labeled "EVIL," while the other showed Satan himself. The interiors, though, were fairly ordinary detective adventure stuff.

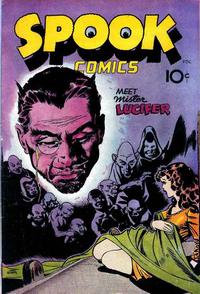

There were also a couple of one-shots in 1946 that bore at least a vague resemblance to horror comics -- Spook Comics #1, from Baily Publications, and Spooky Mysteries #1, from Your Guide Publishing. Spook Comics was more or less detective-adventure stuff; Spooky Mysteries was humor. Both, however, used the imagery of devils and ghost stories.

And I should mention that Classics Comics (later Classics Illustrated) didn't hesitate to adapt classic horror stories, beginning with "The Headless Horseman" in their twelfth issue. (It was a back-up feature to "Rip Van Winkle.") #21 was "3 Famous Mysteries," with a horrific bent; #26 was Frankenstein; #40 was "Mysteries," and adapted stories by Edgar Allan Poe. That brings us to August of 1947; let's pause there and backtrack a bit.

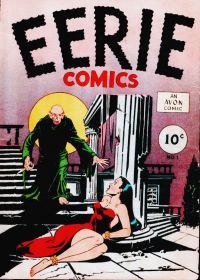

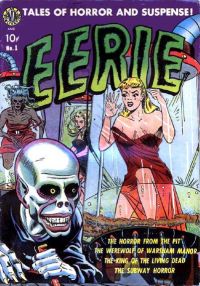

Despite all these warm-ups and experiments, it wasn't until January 1947 that the first real, indisputable horror comic came along -- Eerie Comics #1, published by Avon. It had a striking cover that was, well... eerie, depicting a strange-looking man with a knife on the steps of some sort of ruin, approaching a bound woman. The stories inside were not particularly good, but they were horror, involving were-tigers and the like. It's hard to point to a particular source or inspiration, such as radio or the pulps, as they were not adaptations and didn't take their form from any existing series in another medium.

Unfortunately, there was no second issue. Avon would later publish seventeen issues of Eerie, starting with #1 in 1951, but there was no Eerie Comics #2. I don't know why; presumably #1 didn't sell well.

The astute reader who knows his E.C. legend will notice that this means Avon published a horror comic at least six months before William Gaines inherited the job of publisher from his father, and a full three years before E.C. created their "New Trend" horror titles. Avon was the first horror comic publisher. E.C. wasn't.

It was left to a third publisher, however, a fairly new outfit called B&I Publishing, to produce the first successful horror comic book.

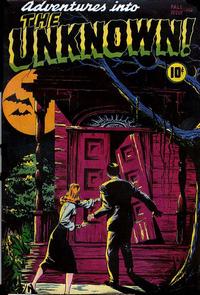

It's hard to imagine what the people at B&I thought they were doing when they published Adventures into the Unknown #1, cover-dated Fall 1948. They had previously published a handful of humor titles, such as Ha Ha Comics and Hi-Jinx, and nothing else but humor. The comics market was crowded at the time, publishers were going broke, and they started a horror title, when no one had ever made a success of horror in comics?

It worked, though. Adventures into the Unknown ran 174 issues, ending in 1967 -- respectable by any standard. The B&I name changed to the much catchier "American Comics Group" with #4 -- ACG, for short.

And they weren't swiping from radio shows, either; behind a dark, moody cover of a young couple approaching a haunted house, that first issue adapted (briefly and badly) Horace Walpole's classic gothic novel The Castle of Otranto, and it was plain throughout the title's early days that the people at B&I were basing their comic books on traditional prose ghost stories, rather than radio drama or earlier comics. I suspect they didn't even know about Avon's attempt the year before, or any of the other previous tries at doing horror in comics form.

(Incidentally, they also started a western title at the same time -- Blazing West. It did okay for awhile.)

At last there was an ongoing, successful horror comic. And E.C. apparently hadn't noticed; E.C. was publishing Gunfighter, Crime Patrol, and War Against Crime.

Or maybe I'm being unfair, because in fact E.C.'s first horror story, "Zombie Terror," appeared in the Fall 1948 issue of Moon Girl, their only superhero title.

Remember I said that the stories in Eerie Comics #1 and Adventures into the Unknown #1 weren't very good? Well, they weren't any worse than "Zombie Terror." That story was an amazingly inauspicious start for a line that would be acclaimed as the best horror comics of all time. And Bill Gaines apparently thought so, too -- E.C.'s second horror story didn't run for another full year.

It's tempting to blame "Zombie Terror" for the fact that after Moon Girl #5 the title skipped a couple of months, apparently on the verge of cancellation, but I'm sure that's going too far.

So Avon had created the first real horror comic, and B&I/ACG had published the first successful one. Was E.C. next?

Nope.

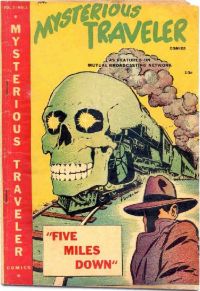

An outfit called Trans-World got in next, in November 1948, with a one-shot based on a radio show. Mysterious Traveler Comics #1, with its bright yellow cover and rather bland stories supposedly told by a mysterious man on a train, doesn't seem to have sold very well. I still feel it necessary to mention it because hey, it was a pre-Code horror comic before E.C. and their imitators.

Ah, yes, those E.C. imitators. In interviews Bill Gaines sometimes spoke disparagingly of the Atlas line of comics, claiming they flooded the market with cheap imitations of E.C.'s horror titles. At first glance the accusation seems reasonable; E.C. published three horror titles to Atlas's thirteen or so. But who was imitating who?

Because the next publisher to get into horror after ACG and Trans-World was Marvel Comics, and Marvel Comics changed their name to Atlas about the time E.C.'s New Trend was getting launched. In short, if anyone was imitating, it was E.C. who imitated Atlas!

Of course, Marvel/Atlas was probably imitating B&I.

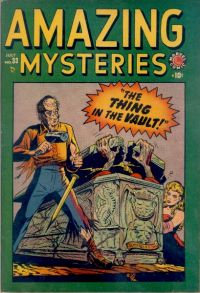

Marvel's first horror issue was Amazing Mysteries #32 -- the numbering came from the just-cancelled Sub-Mariner Comics. Superheroes were dropping on all sides, and Marvel seemed to think that the future lay in horror. In the course of a few months in 1949 they transformed all their top superhero titles to horror.

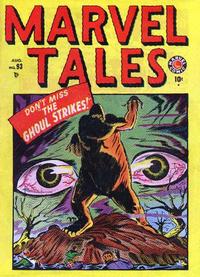

Next after Amazing Mysteries came the transformation of Marvel Mystery Comics, their flagship title, into Marvel Tales, beginning with #93, dated August 1949. Marvel Mystery had featured superheroes; Marvel Tales was all horror.

Captain America Comics became Captain America's Weird Tales with #74, dated October 1949 -- though Captain America still appeared in that one. #75 was entirely horror stories. It was also, alas, the final issue.

In fact, despite their plunge, Marvel seems to have lost their nerve. With its third issue Amazing Mysteries switched to crime stories; the fourth issue, #35, was the last. Captain America's Weird Tales died.

But Marvel Tales flourished. By the time E.C. began trying out "The Crypt of Terror" in Crime Patrol and "The Vault of Horror" in War Against Crime, Marvel Tales had run three issues, and Adventures into the Unknown seven.

So much for the claim that Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein invented horror comics all by themselves.

Incidentally, those early Marvel horror issues really weren't very different from what was to come -- mad scientists, vampires, ghouls, and assorted monsters rampaged through their pages. No gut-sucking mummies or scattered body parts yet, though; the stories were still relatively tame.

Relatively. I'm sure that kids at the time found stories like "The Ghoul Strikes!" (Marvel Tales #93) to be pretty darn exciting stuff.

It may seem as if I've been unduly harsh on E.C. If I have, it's only to counteract the rabid fans who have gone too far in praising them. E.C. did produce the best horror comics of the pre-Code era; they did have a huge influence on the field, and they were widely imitated.

They were not, however, the first horror comics, or the only good ones, or the sole inspiration for the scads of others published between 1950 and 1955.

It may well be that Bill Gaines did not know, in the early days of 1950, that anyone was publishing horror comics. He said he didn't, that he got the idea entirely from radio; I have no reason to doubt his word. Perhaps horror comics were just an idea whose time had come.

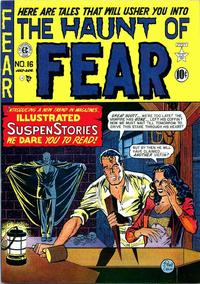

And after Avon, ACG, Trans-World, and Marvel, E.C. was the next to get into the field, in March 1950, when Gunfighter became Haunt of Fear, Crime Patrol became Crypt of Terror, and War Against Crime became Vault of Horror.

Enough has been written about E.C.'s "New Trend" elsewhere that I won't go into it all again. I can't resist pointing out one other bit of false mythology, though. The legend has it that the three horror titles were immediately a huge and obvious success.

Enough has been written about E.C.'s "New Trend" elsewhere that I won't go into it all again. I can't resist pointing out one other bit of false mythology, though. The legend has it that the three horror titles were immediately a huge and obvious success.

Then why were two of the three almost cancelled six months later? Vault of Horror was to be replaced by Crime SuspenStories; Haunt of Fear would become Two-Fisted Tales. Even Crypt of Terror got a name-change, to Tales from the Crypt. It was only at the very last minute, when the covers for Crime SuspenStories #15 (following Vault of Horror #14) were already being printed, that sales figures came in and convinced Gaines to keep the horror titles and add the new titles, rather than switching. Crime SuspenStories #15 was renumbered as #1 midway through the print-run. Two-Fisted Tales kept the old numbering, and Haunt of Fear started over with #4.

Apparently the very first New Trend issues didn't do well -- maybe readers or newsstands didn't know what to make of them. It was the second and third issues that took off.

And those issues did take off.

They didn't set any records -- that's another myth. Oh, they sold better than anything else that E.C. had published up to that point, but E.C. was a small and unsuccessful company. Their sales appear to have been in the 400,000-copy range, where Lev Gleason's Crime Does Not Pay regularly topped half a million. (The cover claim of six million readers for Crime Does Not Pay was based on a survey that indicated after hand-me-downs, trades, and so on, between ten and twelve kids read each copy.)

Some people seem to think that during the early 1950s horror comics were as dominant as superhero comics are now. This was simply not true. At the peak of the market and the peak of the horror craze, in late 1953 and early 1954 (just before the boom-and-bust cycle went bust), there were about 500 titles on the newsstands; about 75 of them were horror -- less than a sixth of the total. The others included superheroes, science fiction, westerns, crime, jungle comics, funny animals, teen humor, romance -- a whole range of genres. Horror might have been the single largest genre for maybe six months or a year in there somewhere, before it all came crashing down; many of those 75 titles were started in '53 or '54 and only lasted a couple of issues. There were probably more westerns even at the peak of the horror craze.

Still, all those disclaimers notwithstanding, starting in 1950 there really was a craze for horror comics. Whether E.C.'s three titles began it or were simply in the right place to cash in on it, I don't know -- nobody does.

Whoever was responsible, plenty of publishers were quick to try to get a piece of the action. Those who were already doing horror had a head start, of course.

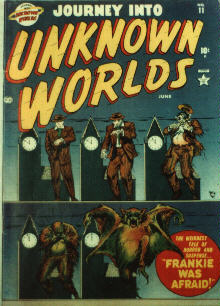

Marvel/Atlas expanded rapidly -- Suspense, based on the CBS radio series, shifted emphasis from crime to horror as of the third issue. A teen humor title, Teen, became Journey into Unknown Worlds as of #36, dated September 1950; Joker Comics became Adventures into Terror as of #43, November 1950. (Both of those later adjusted their numbering.)

Marvel/Atlas expanded rapidly -- Suspense, based on the CBS radio series, shifted emphasis from crime to horror as of the third issue. A teen humor title, Teen, became Journey into Unknown Worlds as of #36, dated September 1950; Joker Comics became Adventures into Terror as of #43, November 1950. (Both of those later adjusted their numbering.)

The Atlas philosophy seemed to be "as much as the market will bear"; when they found something that sold, they'd keep on adding titles until the sales per title actually dropped. (Some things don't change -- or at least, they recur. Atlas is now Marvel, of course, and... well, have you counted how many Spider-Man titles are out there?)

The public's appetite for horror was immense; Atlas kept adding titles for quite some time. When 1951 rolled around they already had Marvel Tales, Suspense, Journey into Unknown Worlds, and Adventures into Terror, but they added Mystic, Astonishing (it started out as a science fiction/superhero title, but switched to horror), and Strange Tales.

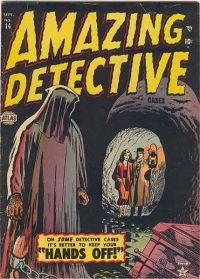

And in 1952 they added Amazing Detective Cases (formerly a crime title, as you might expect, but for its last four issues, #11 through #14, it was pure horror), Adventures Into Weird Worlds, Mystery Tales, Spellbound, Journey into Mystery, and Uncanny Tales.

Finally, in 1953, as the market reached saturation, they only added one title: Menace. And they'd folded Amazing Detective Cases. At their peak, therefore, they were publishing thirteen horror titles. (They dropped Suspense -- probably because they didn't want to continue paying CBS for the license -- shortly after adding Menace; that brought them back to twelve.)

E.C. fans who think Atlas was a mere E.C. imitator will please notice that their titles, as listed above, generally looked a lot more like ACG's Adventures into the Unknown than like E.C.'s Vault of Horror. If Atlas was imitating anyone, it was ACG.

E.C. started with three horror titles, and stayed at three, though they did add Shock SuspenStories, which included some horror, in 1952, and were planning a fourth title, Crypt of Terror, when the market collapsed in 1954. Their two science fiction titles, their crime title, and even their war books often had a horrific tinge, as well.

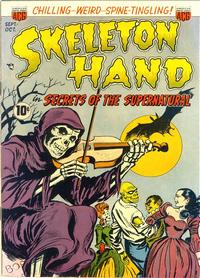

ACG added Forbidden Worlds in the summer of 1951, Out of the Night in early 1952, and Skeleton Hand later in '52. Skeleton Hand only lasted six issues. They also put out a one-shot in 1954, The Clutching Hand #1, that might have originally been intended as Skeleton Hand #7.

And then came the new arrivals. Ziff-Davis, primarily a pulp publisher, was getting into comics, and launched Amazing Adventures in 1950. That was a mix of horror and science fiction.

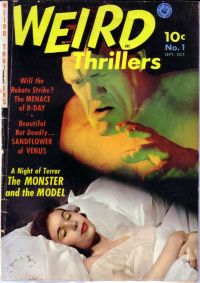

They then tried for a straight horror title. Eerie Adventures #1 appeared with a Winter 1951 cover date, but there was no second issue; apparently Avon, which still owned the name Eerie, objected. Ziff-Davis then tried Weird Adventures #10 (why 10? No one knows), July/August 1951, but that didn't go, either; the next issue was Weird Thrillers #1. That one seems to have been okay.

Their third horror title was Nightmare, begun in the summer of 1952.

All the Ziff-Davis comics were notable for having painted covers, usually far more detailed and realistic than was the norm in comics. The stories were above average in quality, but still well short of E.C.'s level; they seemed to be plotted very much like pulp stories, and it's likely that they were, in fact, scripted by pulp writers. These were not imitation E.C.s; they were, rather, pulp spin-offs. That was obvious at a glance.

All three titles were cancelled in the fall of 1952, for reasons that remain a mystery. They were apparently selling reasonably well -- well enough that St. John bought the Nightmare name, at any rate. Ziff-Davis may have just decided that comics were more trouble than they were worth; the only title they continued was G.I. Joe

Whatever the reason, Amazing Adventures ended with #6, Weird Thrillers with #5, and Nightmare with #2.

The next contender was Ace -- A.A. Wyn's company was involved in magazines, paperbacks, and comics more or less equally at that point, as far as I can tell. A failing romance title, Love Experiences, became Challenge of the Unknown with #6 -- no connection with the later Challengers of the Unknown from DC. There was no #7; the next issue was The Beyond #1, a title that lasted thirty issues.

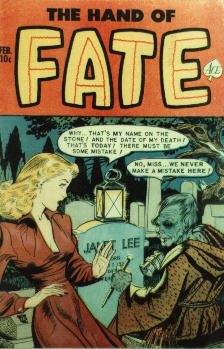

Web of Mystery was added in February 1951, Baffling Mysteries in November '51 (starting with #5; the numbering came from Indian Braves), and Hand of Fate a month later (starting with #8, following Men Against Crime #7). All of those ran until 1955. Were they E.C. imitations? Maybe. If so, they were amazingly bad at it. Especially in the early issues, which were full of stolen pagan religious relics or mysterious cults in odd corners of the world, the plots seemed more akin to the pulp stories in Weird Tales than to anything E.C. published.

Web of Mystery was added in February 1951, Baffling Mysteries in November '51 (starting with #5; the numbering came from Indian Braves), and Hand of Fate a month later (starting with #8, following Men Against Crime #7). All of those ran until 1955. Were they E.C. imitations? Maybe. If so, they were amazingly bad at it. Especially in the early issues, which were full of stolen pagan religious relics or mysterious cults in odd corners of the world, the plots seemed more akin to the pulp stories in Weird Tales than to anything E.C. published.

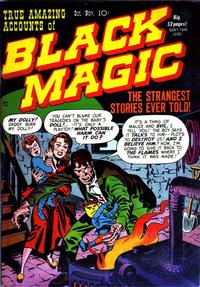

Remember Prize Comics, where "Frankenstein" had appeared back during the war? Well, that was published by the Prize Comics Group, which also operated under the names Crestwood, Feature, and Headline. All the same company, whatever the name. They got into horror with Simon & Kirby's Black Magic, starting in November 1950 -- a title that survived, much transformed and after the occasional hiatus, into the 1960s!

Black Magic was not an E.C. imitation at all; it was, in fact, seriously weird, with the bizarre originality that Joe Simon and Jack Kirby were famous for. The reader wouldn't find vampires and werewolves here, but psychics, freaks, witches, and nameless monsters. This wasn't the world of the pulps, or of radio drama; this was, instead, the world of the tabloids. Prize had something unique here.

It took them until 1952 to realize that they had already had another valuable property all along. When it did sink in they revived Frankenstein Comics, last seen as a humor title, as serious horror, starting with #18, dated March 1952; it lasted through #33.

Prize also produced an odd title, borderline horror, that resulted from Jack Kirby getting interested in Freudian dream analysis -- Strange World of Your Dreams. That started in 1952 and lasted four issues. Like Black Magic, it was an oddball title that took a skewed view of the real world, rather than presenting the standard fantasy world of the comics. Where E.C.'s worldview was cynical, Prize stories seemed credulous and accepting -- one got the impression that the writers actually believed in ghosts and psychic powers.

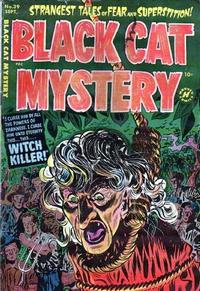

The next publisher to enter the field was Harvey. Harvey had run some mildly spooky stories in the past, such as the Man in Black Called Fate back-ups in Green Hornet Comics, and in January 1951 they got serious about horror with Witches Tales #1. It was apparently a success, because a few months later it was joined by Chamber of Chills and Black Cat Mystery, and in 1952 a fourth title, Tomb of Terror.

Black Cat Mystery took over its title and numbering from Black Cat Comics, a superhero book. The others started from scratch -- I think. Chamber of Chills started with #21, progressed to #24, then dropped back to #5 and went on from there. Usually, this meant the publisher had changed another title but kept the numbering, so as to save the cost of buying another second-class mailing permit for subscription copies -- the reader will have already noticed that a great many titles were created by changing something totally unrelated. However, in the case of Chamber of Chills, I've never found any reference to another title it could have picked up the numbering from, so they may have just started with #21 arbitrarily. This wasn't unheard-of -- Ziff-Davis often started titles with #10, Standard usually started with #5, etc. This was apparently done because, in sharp contrast with modern comics, comics with higher numbers sold better. They were established, they'd survived a few issues, so they must be good, in theory.

The four Harvey titles sold quite well. Were they cheap imitations of E.C.?

Well, yeah, they were. They are, in fact, probably where the general impression came from that the market was flooded with E.C. imitations. Just look at the titles: E.C. had its Crypt of Terror, Harvey had Tomb of Terror. E.C.'s Haunt of Fear featured the Old Witch as a narrator; Harvey published Witches Tales. E.C. had the Vault of Horror, and Harvey had Chamber of Chills. The only one that looks original is Black Cat Mystery, and that was just to save on a second-class permit by changing Black Cat Comics.

Harvey even attempted to imitate E.C.'s distinctive art, with the talented Howard Nostrand swiping Wally Wood's work. When Sid Check drew a story for E.C., Harvey suddenly hired him to draw for them, as well. Several of Harvey's stories stole their plots from E.C.

E.C. stories had a reputation for being shocking and gory. This reputation was exaggerated, as most of their stories were not actually gory (there were exceptions, such as "Foul Play" in Haunt of Fear #19 and "Dog Meat" in Crime SuspenStories #25); the shock usually came from the clever plotting, or by implication, rather than from anything actually drawn there on the page.

Harvey didn't notice this, and believed the reputation -- or maybe they noticed, but realized they couldn't match E.C. on their own terms. Harvey stories often were deliberately shocking and gory, filled with decapitations, dissolving flesh, and the like.

There's one other odd difference between E.C. and Harvey, quite aside from quality or originality. E.C. used vampires, werewolves, ghouls, and other traditional monsters, but there was one traditional sort of supernatural story they never cared for: deals with the devil. I suspect it was because Bill Gaines wasn't religious. E.C.'s worldview was essentially secular, with no place for Hell or the Devil.

At Harvey, on the other hand, devil stories were a staple. They were all over the place. They got quite boring, in my opinion -- but then, I'm not religious, either.

And when people suggest that the Comics Code was written specifically to kill E.C. by banning the words "horror," "terror," "crime," and "weird" from comic-book titles, I sometimes wonder whether they're really thinking about what they're saying. E.C. didn't have a comic book with "terror" in the title in 1954; Crypt of Terror had been changed to Tales from the Crypt back in '50.

But Harvey was still publishing Tomb of Terror. The Code was aimed at Harvey and others as well as E.C.

Harvey, of course, survived the Code by switching entirely to kiddie comics -- Richie Rich, Little Dot, and the like. Their reputation has been so squeaky clean since 1956 that many people I talk to have trouble believing that Harvey, of all companies, could ever have put out truly gruesome comics about ghouls and zombies and the like.

But they did.

And in 1951 the flood began in full force. Companies ranging from the giant National Periodicals (now DC Comics) to fly-by-night outfits that changed names every few months to dodge their creditors began to put out horror comics.

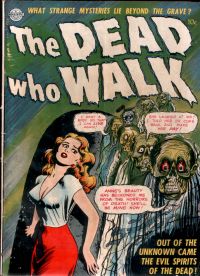

Not every company did; for example, Dell Comics, then the industry leader, was perfectly content with their mix of westerns, humor, and adventure titles. Altogether, though, twenty-eight publishers produced horror comics. Besides those I've already listed, Avon returned; they reprinted stories from Eerie Comics #1 in Eerie #1, beginning a 17-issue run. Their second title was Witchcraft, which lasted six issues; and they produced half a dozen one-shots, most notably The Dead Who Walk, a single story running the entire issue that was genuinely creepy and suspenseful. Avon's horror comics were known for covers depicting skulls, bones, and women in bondage; the interiors often had high-quality art in the style of book illustration, but alas, the scripts rarely lived up to it.

E.C. imitations? I don't think so. Avon was there before E.C., and was just doing more of what they'd started with.

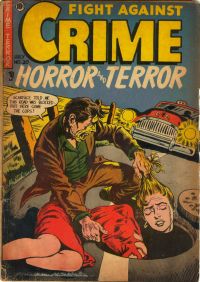

A little outfit known variously as Story, Master, or Merit jumped in in 1951 with Mysterious Adventures and Dark Mysteries, which were generally pretty tacky. Lots of vengeful corpses and skeletons on the covers. They also published Fight Against Crime, a crime comic that gradually progressed from gangsters to axe murderers and homicidal maniacs; the cover scenes switched from shoot-outs to decapitations. The later issues, while still officially having the same title, had covers that read

Fight Against

C R I M E

H O R R O R and T E R R O R

This led some later cataloguers to list it under the title Crime, Horror, & Terror. And yes, though the first few issues were different, they imitated E.C., obviously and deliberately, once they got going -- Fight Against Crime modeled itself after Crime SuspenStories. The first couple of issues of Dark Mysteries looked more like Avon, but by the second year it was clearly aping Vault of Horror.

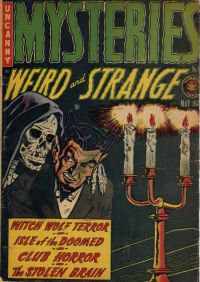

A Canadian publisher, Superior Comics, got into the act with Journey into Fear, Strange Mysteries, and Mysteries. (Mysteries called itself Mysteries Weird and Strange on the cover, but the actual legal title was simply Mysteries.) These had relatively weak art, provided by the Iger Studios production line, and especially in the later issues many of the stories were hackneyed and dull, but some of the earlier tales were bizarre and quirky and very enjoyable. I suspect this was because the writers didn't yet know what they were doing; once they settled into the work that initial odd charm faded. If these were intended to imitate E.C., they weren't very close.

I know almost nothing about P.L. Publications, but they put out three issues of Weird Adventures in 1951 that featured lurid, violent stories with crude art. They were more like the "weird menace" pulps than like E.C. I thought they were fun, but parents in 1951 were probably appalled.

During the horror boom a fellow named Stanley P. Morse had acquired the single most important element of comics publishing at the time -- a distribution contract -- and used it to market comics under a wide variety of names: Stanmor, Aragon, Key, Gilmor (I believe he had a partner named Gilman for that one), mr. publications, S.P.M., Media Comics (not to be confused with Comic Media), and probably others I don't know about. His titles often changed publisher from one issue to the next as he dodged creditors or changed partners, and would sometimes have cover art taken from a story in a different issue as deadlines were missed. If he came up a story short he would simply reprint something. If he couldn't get an artist for a particular slot, he'd have his editor cut up and rearrange the art from an old story to make a new one. Anyone who thought men like Bill Gaines gave comics a bad reputation had never met Stanley Morse. Naturally, he published horror comics, including some of the grossest and most vile.

Mister Mystery ran nineteen issues, and featured several notorious covers -- a white-hot poker approaching a staring eyeball, a man buried up to the neck in an anthill, etc.

Weird Mysteries lasted twelve issues and cover-featured a brain torn from a skull and other such delights.

Weird Chills only lasted three issues, all in 1954. In my decades of collecting and reading comics I think this may be the single most unpleasant title I ever read; #2 featured stories entitled "Violence!" and "Hate," for example.

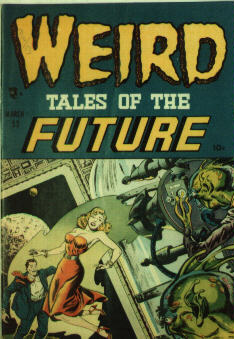

Weird Tales of the Future, on the other hand, was usually fun, with a peculiar mix of science fiction and horror stories, including some covers and stories by the unique Basil Wolverton. (Wolverton had stories in Weird Mysteries and Mister Mystery, as well.) The last issue, #8, was a reprint of Weird Mysteries #12 and is best ignored.

Weird Tales of the Future, on the other hand, was usually fun, with a peculiar mix of science fiction and horror stories, including some covers and stories by the unique Basil Wolverton. (Wolverton had stories in Weird Mysteries and Mister Mystery, as well.) The last issue, #8, was a reprint of Weird Mysteries #12 and is best ignored.

I don't think Morse was trying to imitate E.C.; I think he was trying to top them. Not in quality -- that would never even have occurred to a man like Morse. No, he was trying to outdo them in gore, violence, and shock value.

Fawcett was best known for publishing the adventures of the original Captain Marvel and his family, but they, too, got into the horror craze. Their titles were This Magazine is Haunted, Worlds of Fear (Worlds Beyond for the first issue), Beware! Terror Tales, Strange Suspense Stories, and Strange Stories from Another World (Unknown World for #1; I assume Atlas, publisher of Journey into Unknown Worlds, objected). None of those lasted very long; in 1953 Fawcett finally settled their lawsuits with DC and got out of comics publishing except for the kiddie comics they did under their Hallden imprint. They sold two titles, Strange Suspense Stories and This Magazine is Haunted, to Charlton; the rest were cancelled. A shame; Worlds of Fear was getting interestingly surreal toward the end. The others were pretty run-of-the-mill stuff, loosely modeled after the E.C. format but not directly imitating E.C.'s approach.

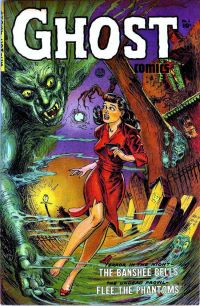

Fiction House was primarily a pulp publisher, but had gotten into comics quite early and stayed there, with at least half a dozen titles at any given time. They'd never gone in for superheroes; straight adventure was their forte. That, and pin-up art -- the term "good girl art" was originally invented to describe Fiction House. Their comics almost all had simple, straightforward titles that didn't much limit what could go inside -- Fight Comics, Planet Comics, etc.

Their longest-running title was Jumbo Comics, which had long since ceased to be any larger than any other comic book by the time of the horror fad; for its final seven issues, numbered #161 through 167, the cover and lead feature were horror, though the rest of the book remained a mix. They also published two issues of Monster, and eleven of Ghost Comics, during the craze. They kept the Fiction House house style, not imitating E.C. or anyone else -- pretty girls, stylish art, bland indistinguishable heroes, and lousy writing.

National, publisher of the DC-Superman line, eventually got in on the fad with House of Mystery. The first few issues were actual horror, with werewolves and vampires, but well before the Comics Code came along they'd switched to stories where some supernatural menace threatens, but is revealed in the end to be an elaborate hoax. This was similar to the old "weird menace" pulp formula, but National/DC systematically removed any trace of sex or sadism -- and the sex and sadism had, of course, been the major selling point of the pulps. I found these stories very tiresome, but apparently the eager young readers in the early 1950s didn't.

Even in the most horrific issues of House of Mystery there was never any gore or shock content. DC ran a clean, inoffensive line.

They also converted their long-running title Sensation Comics, formerly home to Wonder Woman, to a "mystery" title -- I can't quite bring myself to call it horror. Three issues after the switch it was given a new title to reflect the change, Sensation Mystery, but it doesn't seem to have helped; the last issue was #116, dated July/August 1953.

DC also tried a hybrid of sorts, a supernatural superhero called The Phantom Stranger who mostly debunked phony ghosts, but who was apparently a ghost himself. That lasted six issues. It also wasn't really anything very new; Marvel had had The Witness, Harvey had the Man in Black, and so on, all the way back to Trans-World's Mysterious Traveler. The Phantom Stranger is interesting mostly because he's still around, though in substantially different form.

Imitate E.C.? Well, possibly at first, but by the third issue of House of Mystery they'd definitely reverted to the DC house style.

Charlton was always something of a second-rate comics publisher -- not bottom-of-the-barrel like Stanmor, but they never quite made the big time, either. They were a bit slow to pick up on horror, but when they did they went at it full-force.

The Thing! began in 1952 and lasted seventeen issues, featuring the Thing (never seen clearly) as a narrator. Although there was an obvious E.C. influence, the stories got wilder than anything the tightly-controlled E.C. crew ever produced.

Their other horror titles were sort of second-hand. A crime title, Lawbreakers, was transformed into Lawbreakers Suspense Stories, and as such lasted six issues, some of them with truly bizarre covers -- the one where a maniac's holding a handful of severed tongues (shown here) is particularly memorable, though the woman eaten alive by moths is also striking. Then Charlton bought the name Strange Suspense Stories from Fawcett, and gave it to Lawbreakers Suspense Stories for its remaining seven issues. (When the Code came in it was retitled This is Suspense! for four issues, then switched back to Strange Suspense Stories.) (Sorry the illustration isn't clearer; it's scanned from a photo, not the original book. I sold my copy a few years ago.)

Their other horror titles were sort of second-hand. A crime title, Lawbreakers, was transformed into Lawbreakers Suspense Stories, and as such lasted six issues, some of them with truly bizarre covers -- the one where a maniac's holding a handful of severed tongues (shown here) is particularly memorable, though the woman eaten alive by moths is also striking. Then Charlton bought the name Strange Suspense Stories from Fawcett, and gave it to Lawbreakers Suspense Stories for its remaining seven issues. (When the Code came in it was retitled This is Suspense! for four issues, then switched back to Strange Suspense Stories.) (Sorry the illustration isn't clearer; it's scanned from a photo, not the original book. I sold my copy a few years ago.)

They bought This Magazine is Haunted outright, continuing the numbering from the Fawcett version.

This Magazine is Haunted and Strange Suspense Stories lacked the over-the-top charm of The Thing! and Lawbreakers Suspense Stories; I really don't know why.

A small but respectable comics publisher was Toby Press, which also used the imprint Minoan; they put out one issue of Tales of Terror, then got hit by a cease-and-desist order from E.C., which used that title for their annuals. Toby dropped that and started over with Tales of Horror, which ran thirteen issues. Toby may be the only comics publisher to swipe the urbane and cynical stories of John Collier, rather than relying on Poe, Lovecraft, and the like, but other than that their horror stories were undistinguished -- and not particularly like E.C.

For the lover of esoterica, Toby also put out three issues of The Purple Claw, one of the stranger supernatural superhero series.

Star Comics was run by L.B. Cole, a man who put great faith in bright colors and striking cover designs as a sales device, and didn't worry very much about what he was selling with them. A typical Star issue would have an eye-catching surreal cover in swirling black and orange and green, one pretty decent horror story by Jay Disbrow, and a bunch of reprints from old jungle comics to fill out the rest of the pages. Numbering was erratic, and titles sometimes didn't have much to do with contents.

Star didn't imitate E.C.; Cole had his own ideas.

The titles were Startling Terror Tales, Terrors of the Jungle (a hybrid, at least in theory, but mostly a jungle title), Shocking Mystery Cases, Terrifying Tales, Spook, Horrors of Mystery (a one-shot in a series called The Horrors; this one, #13, was the only actual horror comic in the series), and the confusing Blue Bolt Weird Tales and its successors. Blue Bolt Weird Tales took over from a superhero called Blue Bolt, then became Weird Tales (despite the existence of the pulp with that name), and wound up as Ghostly Weird Stories (probably because the publishers of the pulp Weird Tales protested).

There were also two issues of Shock Detective Cases that were on the border between crime and horror.

And a few others were announced or advertised, but never appeared. Star had this annoying habit of advertising titles, then deciding whether or not to actually publish them based on the response.

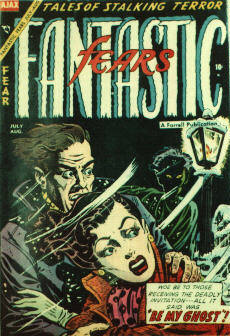

Farrell Publications could be annoying, too. For one thing, they sometimes labeled their products as "Ajax Comics," sometimes as "A Farrell Publication," and sometimes as both. Confusing. Their horror titles were Voodoo, Haunted Thrills, Fantastic Fears, and Strange Fantasy. They were all pretty cheesy, but the covers could be interestingly strange, with skeletons feasting or women in test tubes or other odd images. And Strange Fantasy has a peculiar history -- the first two issues are both #2, apparently simply by mistake, and the cover of #9 was overprinted and used to bind a bunch of leftovers, so that anyone who bought it might get the horror comic he expected, or might get an issue of Boys Ranch or Black Cat from the Harvey warehouse. (Why Harvey? I don't know. No one does. Records are mostly long since lost.)

Farrell Publications could be annoying, too. For one thing, they sometimes labeled their products as "Ajax Comics," sometimes as "A Farrell Publication," and sometimes as both. Confusing. Their horror titles were Voodoo, Haunted Thrills, Fantastic Fears, and Strange Fantasy. They were all pretty cheesy, but the covers could be interestingly strange, with skeletons feasting or women in test tubes or other odd images. And Strange Fantasy has a peculiar history -- the first two issues are both #2, apparently simply by mistake, and the cover of #9 was overprinted and used to bind a bunch of leftovers, so that anyone who bought it might get the horror comic he expected, or might get an issue of Boys Ranch or Black Cat from the Harvey warehouse. (Why Harvey? I don't know. No one does. Records are mostly long since lost.)

Farrell was one of the companies to survive the Comics Code, at least briefly, and managed it in part by transforming Fantastic Fears to Fantastic, and Voodoo to Vooda, "Vooda" being the name of a "jungle goddess."

Youthful Magazines only had one horror series, but three titles. They started by changing the science fiction adventure series Captain Science to Fantastic; that lasted two issues, and then became Beware.

Beware was, as I understand it, packaged by Harry Harrison for Youthful. Harrison had started out as an artist and worked his way up to editor/packager; later, when the comics industry collapsed, he took up writing science fiction instead, and has done very well for himself at it. Back then, though, he was putting together Beware. And after three issues at Youthful, Harrison took the title over to Trojan.

Youthful didn't give up, though; they kept the numbering and found someone else to produce Chilling Tales for another five issues.

Then they gave up, in October 1953.

What's odd is that each of the three titles has a distinctly different flavor. Fantastic was a crude mix of science fiction and horror; Beware was an E.C. swipe, much slicker than Fantastic; and Chilling Tales had an almost primitive style, with plots borrowed from anywhere at hand, including some E.A. Poe adaptations, not unlike the very early issues of Adventures into the Unknown.

St. John was a mid-sized comics publisher with a varied list of titles, and in June 1952 they joined the horror binge with two titles, Strange Terrors and Weird Horrors. Strange Terrors ended after seven issues, to be replaced by Nightmare #3, picking up from the Ziff-Davis series. However -- and I can't explain this, only report it -- they then combined the title Nightmare with the numbering from Weird Horrors, so that Weird Horrors #9 and Nightmare #3 were followed by Nightmare #10. And after Nightmare #13 the title was changed to Amazing Ghost Stories for its final three issues.

St. John was also heavily involved in the fad for 3D comics, so it's not surprising that they published the first 3D horror comic, House of Terror #1, in October 1953.

St. John was fond of zombies -- even if they didn't always know how to spell it; they're famous for a cover typo spelling it "zoombies." They're also notable for having some fine Joe Kubert art, and for publishing all the known art by someone signing himself "Ekgren." Ekgren did two Weird Horrors covers and one for Strange Terrors in an intricate, mazelike, hallucinatory style unlike anything else in the comics of the time -- though it might not have looked so out of place in 1960s undergrounds.

The early St. John issues seem to have tried to imitate E.C. and Atlas, but that didn't last; the covers by Ekgren and Kubert weren't like anything any other publisher was doing.

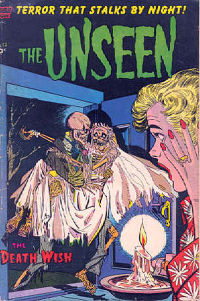

Standard Comics did not believe in #1 issues. They were convinced that comics sold better if they appeared to have been around for awhile, and therefore they started all their horror titles with #5. Those titles were The Unseen, Out of the Shadows, and Adventures into Darkness, each lasting about ten issues of fairly well-done E.C. imitations. They also produced a suspense one-shot, Who Is Next? #5, that deserves mention -- it features a town terrorized by a serial killer.

Comic Media had no connection with Stanley Morse's Media Comics. They were a respectable publisher that produced two horror titles, Weird Terror and Horrific, that ran thirteen issues each. The odd thing about these titles is that the publisher was convinced that faces sold comics; after the first two issues of each he insisted that every issue have some sort of a face dominating the cover, and Don Heck, his cover artist -- yes, the same guy who was a key part of the Marvel crew in the 1960s -- obliged. Werewolf faces, monster faces, terrified faces -- but always faces. It makes Comic Media comics rather noticeable.

Oh, yeah -- Horrific became Terrific for a fourteenth pre-Code issue. With a big scary face on the cover.

The covers weren't like E.C. at all, but the stories, alas, were insipid E.C. imitations.

Hillman Comics is not one of the twenty-eight publishers who produced horror comics. They did, however, acknowledge the craze to the extent of putting horror covers on two one-shot crime titles, Monster Crime #1 and Crime Must Stop! #1. I wanted to mention that particular oddity in passing.

Quality Comics was a major player in the superhero days of the 1940s, but they were in decline by late 1952, when they launched Web of Evil, their only horror title. It lasted twenty-one nondescript issues before the company sold out to National. The stories were too bland to identify as imitating anyone in particular.

Trojan, like Hillman, tried putting horror covers on crime comics -- they pulled the stunt on Crime Mysteries and to a much lesser extent on Crime Smashers. They even snuck a few actual horror stories inside toward the end of the run of Crime Mysteries, too. They didn't try starting their own horror title, though; instead they bought Harry Harrison's Beware away from Youthful Magazines.

They didn't get the second-class mailing permit with it, though, so after numbering the first four issues #13 through 16 they started over at #5. This resulted in some confusion, as there are two each of #13, 14, and 15, all from Trojan, but with different dates. (There are also two each of #10, 11, and 12, but from different publishers.)

There's only one of #16, though, because the second #15 was the last issue.

As it had been at Youthful, the Trojan Beware was an E.C. imitation, even going so far as to use cover art on #6 that appears to have been partially traced from a Jack Davis Vault of Horror splash panel.

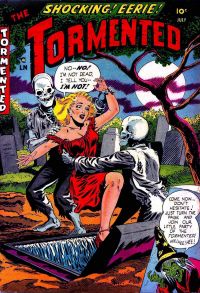

Sterling was a very small company just trying to get started in 1954 -- which turned out to be bad timing, as the whole comics industry went through a major collapse in 1955-'57. They produced two horror issues before the Comics Code arrived: The Tormented #1 and #2. Both featured pretty girls in red dresses on the cover, and stories with above-average art but plots that were hardly new or exciting any more. #1's best story is a cannibalism tale that would have been unspeakably shocking in 1950, but by this time, in 1954, readers were jaded.

And finally, Premier got started just in time to put out one issue of true pre-Code horror -- but it's a beauty. Horror from the Tomb #1, September 1954, is an over-the-top delight, absurd and funny and frightening all at once.

Premier didn't cancel it; with the second issue it became the cleaned-up Mysterious Stories, and with #3 it was Code-approved; #7 was the last.

And that's the complete list of pre-Code horror publishers. Oh, a case might be made for including a couple of others, I suppose, but that's all the definite ones.

Quite a lot of them, weren't there?

Too many, in fact; the field was overcrowded. And with all those publishers trying to top one another, the stories had gotten pretty nasty. Dismemberment and cannibalism were commonplace -- old hat, in fact. One E.C. story hinted strongly at actual necrophilia -- in 1954! Readers were jaded -- and parents were furious.

Complaints about comic books weren't new; there had been articles denouncing comics in the popular press as early as 1940. Comics were described as shoddy, debased, semi-literate; they were accused of keeping kids from reading real books, of giving kids false ideas. The urban legend about the kid who tied a towel on as a cape and jumped out an upstairs window, thinking he could fly like Superman, dates back to at least 1944.

But nothing had been done about it before.

Then came Dr. Frederic Wertham.

Ah, Dr. Wertham, the traditional villain of the piece! So just who was he?

Frederic Wertham was a psychiatrist who fled Germany in the 1930s and wound up in New York, where he eventually landed himself a job as a court psychiatrist -- I have the impression that he had failed to make it in private practice, but I admit I can't document that. His job was to interview criminals to determine why they had committed crimes, and whether they were sane enough to be tried. He first came to public notice when he happened to be the man assigned to interview Albert Fish.

Albert Fish was a serial killer -- though the term didn't exist at the time -- who had preyed on children with impunity for years by confining his attentions to poor black victims. When he made the mistake of killing and eating a middle-class white girl, however, he was caught, tried, convicted, and executed.

Fish was big news for a time -- New York hadn't had any other cannibals that anyone knew of. Furthermore, Fish was quite spectacularly deranged; as well as being a child molester, murderer, and cannibal, he was both a sadist and a masochist, and among other quirks had permanently embedded straight pins in his own flesh. And Wertham was the expert who interviewed him and described him to the press.

Wertham loved the attention. And the press loved Wertham when he told them that Fish had practiced every perversion known to Man and had maybe invented some new ones.

Wertham followed up this opportunity by writing a lurid book about the criminals he had interviewed: Show of Violence. It did fairly well.

However, the authorities in New York don't seem to have been particularly happy about it, and Wertham was reassigned to work with juvenile offenders -- or as they were known at the time, juvenile delinquents. I assume this was done so that he wouldn't have anyone as spectacular and embarrassing as Fish to write his next book about.

So Wertham began interviewing J.D.s about their home lives, their spare time activities, and so on, trying to find out why they'd gone bad.

One fact that struck him quickly was that they all mentioned reading comic books, and most of them specifically mentioned reading crime comics. It's not really surprising that Wertham theorized that crime comics had contributed to their delinquency.

If he'd done the same thing ten years later, they'd all have mentioned watching TV -- and we have plenty of people now blaming TV for violence. In 1949 and 1950, though, slum kids didn't have TV.

Dr. Wertham was a doctor, not a scientist; he didn't think to test his hypothesis or look for flaws in it. He didn't find a control group of normal kids and ask if they read comics -- they'd have said "yes," because back then virtually all American kids read comics. Instead, he only began looking for supporting evidence.

None of the law-abiding adults he talked to had read comics as kids -- because there hadn't been comic books when they were kids. He remembered German kids as being well-behaved, and they had no comic books, because comic books were an American invention.

Wertham began collecting comics as evidence. Not horror comics -- crime comics. The kids said they read crime comics.

Except Dr. Wertham had never entirely gotten the hang of American society or American English; to him, any book with criminals in it was a crime comic. Superheroes fought criminals; therefore, superhero titles were crime comics. Vampires and werewolves kill people, so they're criminals, so horror comics were crime comics. Westerns involve rustlers and train robbers, so those, too, were crime comics.

And the final result of Dr. Wertham's "research" was a book entitled Seduction of the Innocent, published by Rinehart & Co. in 1954 and chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club as one of their leads. This book was sensationalistic in the extreme, aimed directly at parents, trying to convince them to keep their kids away from "crime comics" by any means necessary.

It didn't attack horror comics as such; they were lumped together with all the other "crime comics." E.C. was not singled out for special attention. Yes, the final panel from "Foul Play," from Haunt of Fear #19, was included -- but that was really an exceptionally gory and tasteless crime story, with no supernatural element. The other E.C. material he used all came from Crime SuspenStories -- their crime title. Other publishers, such as Superior, were hit just as hard, and the illustrations included panels from westerns and even romance comics, but were mostly from crime, rather than horror, comics.

The companies that depended on crime titles, such as Lev Gleason, got slammed much harder than any horror line.

You'll notice that while horror comics survived, admittedly in watered-down form, there are no more true-crime comics, and except for a few low-circulation oddities there have been none since 1956. Wertham wasn't aiming at E.C. or at horror comics; he was after crime comics. And he got them. Horror just got caught in the overkill.

And boy, was there overkill!

The 1950s were a paranoid era. The United States was the most powerful country in the world, and intended to stay that way; any perceived threat to the "American way of life" was attacked all-out. Communist conspiracies were seen on all sides (and a few of them were actually there).

Dr. Wertham and the other anti-comics crusaders managed to make the American public perceive comics as a threat.

It wasn't Wertham alone, by any means; the New York state legislature had investigated crime and horror comics back in 1951, before Wertham's book was written, and had denounced them. (In fact, New York belatedly outlawed them in 1955, a law that may still be on the books but has been ignored for decades.) Other crusaders -- for literacy, for decency, for other causes -- had attacked comics for years. But Seduction of the Innocent seems to have been the final trigger for public outrage. Comic book publishers received threatening letters, parents complained to store managers about their comics displays, legislators heard from angry constituents.

And Senator Estes Kefauver decided to do something about it.

(Some fans lump the comics censorship movement with McCarthyism; this is inaccurate. Dr. Wertham was driven out of Germany as a suspected leftist and would hardly have been in McCarthy's camp, and the senator who went after comic books was Estes Kefauver, not McCarthy.)

The Senate created a committee to investigate comics publishing, and invited publishers to testify on their own behalf; only Bill Gaines actually did testify, while any number of "experts" spoke against comics and other publishers began looking for a way out of the mess. That part of the E.C. legend is true.

In the end, the Senate committee did nothing -- not because they were swayed by Gaines, whose testimony turned into a disaster, but because those other publishers back in New York found a way out. They staged a public housecleaning and created the Comics Code Authority. Given a choice between cleaning up their own act or facing government intervention, they chose to censor themselves.

It's hard to say, in retrospect, whether this was a cowardly move that ruined comic books, or a wise decision that kept comic books from being totally destroyed. Would the U.S. government have intervened directly, and unconstitutionally, to stamp out crime and horror comics?

They might well have done exactly that. Things were different in 1954.

At any rate, all the major publishers except Dell and Gilberton joined the CCA. Dell had such a squeaky-clean reputation that they didn't need to bother; Gilberton, publisher of Classics Illustrated, seems to have been considered a special case by everyone involved and was deliberately left out.

Some of the minor publishers did not join; instead they went out of business.

However, it wasn't necessarily the Code that killed them. The comics market was declining at the time anyway, and at very nearly the same time that the Code came in there was a major shake-up in the magazine distribution system -- the American News Company, by far the largest distributor in North America, was liquidated by its stockholders. The result was that the other distributors didn't have the capacity to handle all the magazines being published, and were able to pick and choose which they would handle.

Naturally, they picked the more profitable ones.

That was what finally killed off the pulps; they'd been fading for years, and the distribution realignment finished them off. Fiction House folded completely; several other pulp publishers managed to get into publishing "slicks," as the glossy, higher-priced magazines were called.

Comics were more profitable than pulps, surprisingly -- even at a dime each, you could fit so many in a bundle that they were still worth shipping. They weren't much more profitable, though; titles and whole companies vanished.

And fans, then and later, who knew nothing about the business side, blamed these extinctions on the Comics Code.

So what did the Code do? Well, it banned the words "Weird," "Fear," "Horror," "Terror," and "Crime" from comic-book logos. It required that every story end with good triumphing over evil. It required that women not be depicted in an exaggerated or titillating manner. It outlawed depictions of vampires, werewolves, or zombies. It basically tried to legislate decency and good taste into comic books -- decency and good taste as defined by polite society in 1954.

That killed crime comics -- but it didn't kill horror comics, not really.

Oh, it watered them down -- you couldn't even call them horror comics any more, after all; they were now "mystery" comics, or monster comics, or suspense comics, or ghost comics.

But they did survive -- some of them. The granddaddy of them all, ACG's Adventures into the Unknown, continued just fine; in fact, the editor claimed to be pleased with the change, saying that he was tired of vampires and zombies and that the new rules forced some originality into the stories.

Atlas had to drop some titles -- Adventures into Terror and Adventures into Weird Worlds were out -- but others continued. Mystic, Marvel Tales, Mystery Tales, Spellbound, Strange Tales, Journey into Mystery, Astonishing, and Journey into Unknown Worlds all continued for years under the Code seal.

Avon gave up comics entirely to concentrate on paperbacks. Ace stuck it out until the distribution crisis forced them out, but all their horror titles had at least one Code-approved issue. That was the story almost everywhere -- a few cleaned-up, Code-approved issues, sometimes with a title change, and then the distribution crunch would kill the series, and sometimes the entire company, off.

A few didn't even try to get past the Code, though; Stanley Morse shut down in the fall of '54. The ban on the word "Weird" might well have been aimed specifically at his products, rather than E.C.'s relatively tame SF titles.

And of course, those that survived and got the Code seal were tame by comparison with what had gone before -- no more rotting corpses, no more scattered body parts, no gut-sucking mummies or dissolving flesh or spouting blood, no cannibal feasts or double-twist shock endings.

But would those have continued anyway? Sales were dropping in 1954 even before the full force of the censors hit; titles were already being cancelled. The horror fad was already burning itself out, and comics publishers were already in trouble. The distribution crisis would have been just as deadly without the Code.

It's impossible to say what would have happened without the Code. Yes, it watered down the field; yes, it may well have prevented a revival of horror comics in the 1960s; but the pre-Code boom was probably doomed anyway.

While it lasted, though, kids across America were treated to a phantasmagoria of twisted pleasures -- not just E.C.'s relatively sophisticated work, but hundreds of weird and wild stories across a whole range of quality and concepts.

They were, as Nostalgia Press said about the E.C. books, "terrifying, shocking, sensational, appalling..." They were also often gross, sometimes disgusting.

And they were, above all else, fun.

The above article was originally published, with somewhat different illustrations, in The Scream Factory #19, Summer 1997 -- the final issue of a fine magazine. Minor corrections have been made for this version.

All text is copyright by Lawrence Watt Evans.

All rights reserved

No reproduction permitted without permission of the author